Allen R Williams, Ph.D., Soil Health Academy Instructor

The 1859 novel written by Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities, was required reading for millions of school kids in English Literature classes and is one of the best-selling novels of all time. The story is set in the late 18th century against the background of the French Revolution. Just as there were challenging times then, we are facing challenging times once again.

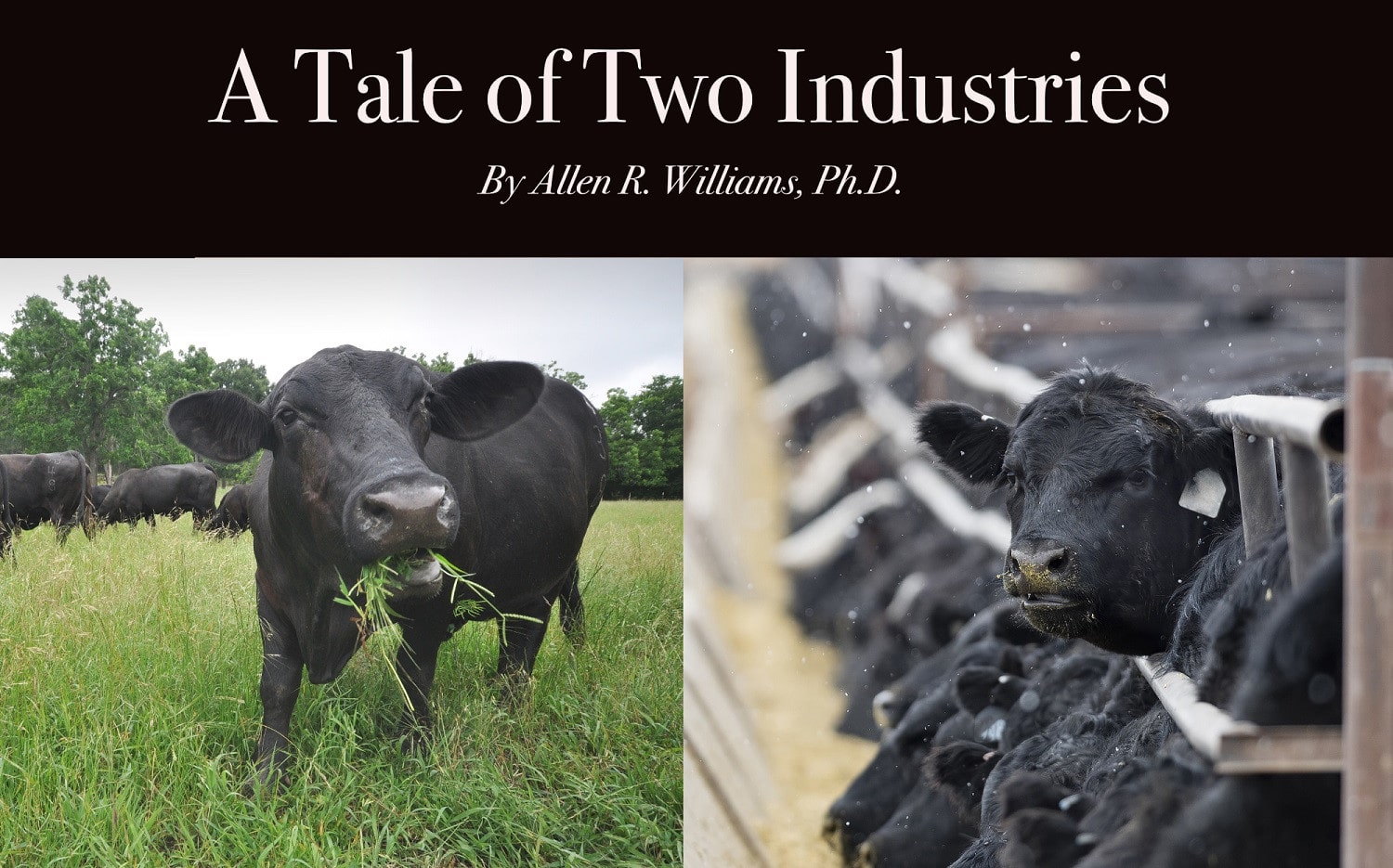

In the face of the current pandemic created by COVID-19, we are left with two distinctly different versions of the same industry. The agricultural industry in the U.S., and particularly the meat industry, have clearly diverged into very different entities. There is the commodity meatpacking industry comprised of the big packers and vertically integrated companies. These companies control more than 85% of all the meat and poultry that hits the grocery store shelves and restaurants. On the other side of the spectrum, there are regenerative farmers and ranchers who produce nutrient-dense proteins and market those to the consumer, either through direct-to-consumer markets, or through branded programs.

Commodity Agriculture

The commodity sector has experienced an array of significant challenges starting with breakdowns in transportation, inadequate cold storage within the retail grocery and restaurant sectors, as well as a breakdown within the packing plants. If you have never been in a major packing plant (beef, pork or poultry) it is quite impossible to social distance and maintain reasonable levels of productivity. The entire model is based on high-capacity plants reliant on an assembly line style that necessitates workers be in close contact throughout their shifts. The plant itself becomes a cauldron for rapid multiplication of any virus. Many of those plants are dependent on a work force comprised largely of immigrants who are seeking a better way of life and who support their families back in their home countries. While working here in the U.S., they tend to live in larger groups in order to save money to send back to their loved ones. That means they have difficulty social distancing either while at work or when at home.

We have seen headline after headline of plants being shut down for periods of time or operating well under capacity—headlines such as “Meat Plant Challenges Expand,” “Meat Shortages Looming,” “US Coronavirus Hotspots Linked to Meat Processing Plants,” “Covid-19 Detected at 115 Meat Processing Plants,” and the list goes on and on. This has not only created issues with processing beef, pork, and poultry for the consumer, but it has also created tremendous economic woes for the farmers producing these commodity proteins. Beef producers are experiencing woeful prices for their live animals while food prices have logged their biggest jump since 1974. Retail beef prices continue to rise while ranchers are taking it in the shorts. The situation seems counter intuitive, yet it is reality.

Hog producers are in even worse shape. Many cannot even give their harvest-ready pigs away (and a number have tried). They have great cost in infrastructure and cannot get paid for their pigs, or they get a price so low they cannot make their loan payments. The commodity pork sector is euthanizing tens of thousands of pigs and aborting pregnant sows. These are animals that were to become food for the consumer and instead end up in landfills and compost piles. A single pork processing plant in Minnesota opened back up after being shut down by coronavirus cases simply to euthanize up to 13,000 pigs per day.

The commodity poultry sector has seen millions of chickens euthanized and fertile eggs destroyed. Their processing plants are experiencing similar issues to the large beef and pork plants.

In a very recent article in Meatingplace.com titled, “Meat plant challenges expand”, one quote from a letter sent to President Trump from a bipartisan group of legislators stated, “Even as plants begin to reopen, meat and poultry plants are expected to operate below maximum capacity for the foreseeable future in order to maintain appropriate public health and worker safety precautions meaning that, unfortunately, depopulation will continue.”

Another Meatinglace.com article the same week titled, “Signs of recovery in beef packing…but how fast” stated that “In the five weeks ending May 9, total beef production was down nearly 690 million pounds year over year.” The author went on to say that the new safety measures and work protocols in beef plants will certainly reduce capacity compared to pre-COVID-19 levels for quite some time.

Prices for several food categories have increased since COVID-19, including meat, poultry, eggs, fish, dairy, fruits and vegetables, and cereal and baked goods. Through May 3, 2020 grocery store meat department sales were up 23% after experiencing eight straight weeks of double-digit growth.

Even before the pandemic, farms across the U.S. were already experiencing a significant increase in bankruptcy filings. According to the American Farm Bureau Federation, year-over-year Chapter 12 farm bankruptcy filings were up 23% at the end of March 2020. COVID-19 issues are expected to accelerate those numbers. There have been five consecutive years of increased farm bankruptcy filings with little hope for an abatement in 2020 or 2021.

A new COVID-19 bill has been passed by the House of Representatives that would compensate farmers for livestock and poultry depopulation due to processing plant capacity reductions. Additionally, the bill would offer direct payments to farmers suffering losses from market disruptions. The National Pork Producers Council (NPPC) hails the bill as a lifeline to struggling commodity pork producers. The NPPC believes up to 10 million hogs may be euthanized within the coming months.

Regenerative Agriculture

In stark contrast, the regenerative agriculture sector is experiencing a boom in sales with little to no price depression. Demand for regeneratively produced foods is at an all-time high. This includes pastured beef, pork, poultry and eggs, lamb, along with vegetables and fruit, grains and herbs. Regenerative farmers are experiencing unprecedented requests from customers. Many have seen sales increases from 400% to over 1200%.

No one in the regenerative sector is euthanizing animals. No one is aborting pregnant sows or destroying fertile eggs. No one is wondering what to do with stocker or feeder cattle until they can be placed into a feedlot. We actually need more of everything.

Demand by consumers is not our issue. Rather we are hitting a roadblock with processing capacity. Not because our processors are shut down because of COVID-19 cases among their employees, but because they are operating way over capacity. They simply cannot handle the increase in demand. They are not suffering economic loss due to inhibited business, rather business is exploding. Many are actively hiring new workers and exploring options to expand their capacity.

Demand for qualified feeder calves, pigs, lambs, and chickens has created shortages that affect regenerative farmers ability to continue to supply their customer base. This opens up opportunity for more farmers to transition from commodity to regenerative agriculture.

Regenerative farmers are not suffering from rising levels of bankruptcy filings. We are not suffering price depression for our cattle, sheep, pigs, eggs, chickens or dairy products. The majority of us do not need stimulus funds to keep our farms operating and profitable. Unlike the commodity sector, the majority of us are not raising our prices in order to take advantage of the consumer. Our prices are reflective of our true costs of production.

Regenerative farmers are not taking away from rural economies but restoring them. We are not exploiting labor but are offering unique opportunities for professional growth. We are not damaging consumer confidence, we’re rebuilding it. We are not damaging our ecosystem and climate, we’re repairing it.

Summary

We are truly experiencing a “Tale of Two Industries.” The contrast could not be more obvious. The question is not whether regenerative agriculture works or if it can be scaled. We already know the answers to those questions. The question is what will we, as a consuming public, do after the pandemic is over? Will we revert back to our old way of food production, processing and eating? Or, will we remember this lesson and take the opportunity to build a resilient food system that can withstand the challenges of a future pandemic? Will we determine that nutrient-dense foods are the key to human health and ability to maintain strong immune systems?

The answers to those questions will determine our collective futures. Clearly, we must regenerate our thinking and our actions, both as consumers and producers, if we are to build a better, healthier and more resilient food system.

The Dickens novel I referred to above begins with the famous line: "It was the best of times. It was the worst of times." Currently, it seems these are the worst of times. But if we endeavor to regenerate our thinking, our actions, our farms, our ranches and our food system, we may, indeed, be able to experience the best of times.