Stemple Creek Ranch - Marin County, California

Stemple Creek Ranch is located in Marin County, California, just north of Tomales. Centered in the coastal hills of northern California, it is a beautiful, but challenging place to ranch at times. Representing the ranch’s fourth generation, Loren Poncia and his wife, Lisa, currently operate Stemple Creek Ranch. They have put considerable effort into reinventing the family business, applying regenerative production strategies and adaptive stewardship, with a vision of raising superior quality pastured proteins. Their daughters, Avery and Julianna, along with their cousins, will be the family’s fifth generation to steward the land.

Overview

Stemple Creek Ranch raises and sells grass-fed beef and pastured lamb, pork and poultry. They are in their 14th year of grass-fed beef and lamb production with pastured pork and poultry production added during the past five years. The production within each enterprise has mostly grown organically and over the years; as demand increased, they’ve responded by expanding production and cultivating relationships with cooperating producers.

When Loren and Lisa started Stemple Creek Ranch, they operated on 600-800 acres. Now they own about 1,000 acres and lease approximately 5,000 more, almost all of which are managed regeneratively as grazing land.

About 4,000 acres of their 6,000 total acres are in what Loren calls “mama cow” or “yearling country,” characterized as rougher rangeland with variable vegetation. They have about 1,500 acres dedicated to their beef finishing enterprise, with 400 acres allocated for the sheep flock, and 20 acres for pasture-raised hog production.

Loren, Lisa, Avery and Julianna

They have 280 cows in their breeding herd and contract with a neighbor who has 350 cows, all of which provide the core supply of feeder calves for their grass finishing operation. When necessary, they purchase finished cattle from cooperators’ herds around the country but the cooperators must agree to use Loren’s approved genetics and manage their herds similarly.

Loren focuses on moderate-framed Angus and Red Angus cattle, the typical finished animal weighing between 1200-1300 lbs at harvest. He also focuses on finishing heifers and steers born on their ranch, but all outside feeder cattle are heifers. Loren does all his grass finishing on site, so he likes to buy heavy feeders (800 lbs+) and targets finishing them in six months to a year.

Sheep Flock on Pasture

They have about 350 ewes that they lamb out each year. All lambs, except the replacements, are grass finished and harvested for their direct-marketing program, selling the equivalent of 1,000-1,500 lambs per year in the meat. Since their 350 ewes do not produce all the lambs they need, they purchase additional feeder lambs from cooperating producers to finish on the ranch.

When they first began direct marketing animal proteins, many customers requested bacon. Loren began with just 10 pigs and today the pasture-raised pork enterprise harvests 200 pigs annually. Because Loren doesn't want a farrow-to-finish program, he purchases weaned pigs and finishes them on the ranch, supplementing pasture forages with a barley and pea mix. The breed type used in the Stemple Creek program consists of Berkshire and Landrace crosses.

As Stemple Creek Ranch grew, they purchased the Burbank Ranch, which is contiguous to the Poncia Family home ranch. They also started leasing additional pastures in Shasta, Sonoma, and Humboldt Counties in Northern California to support herd expansion. Loren said that these leased pastures keep their cattle on fresh green grass on a nearly continuous basis.

Because it takes longer for cattle to reach harvest weight, grass-finished beef costs more than conventionally produced beef. Conventionally produced beef animals are harvested at 14-18 months of age but Stemple Creek Ranch waits until 24-28 months of age, harvesting at weights ranging from 1,200-1,350 pounds. “The longer the cattle live and grow happily on the land, the more flavorful and higher quality the meat will be,” Loren says. “This is just one of the reasons our customers tell us our meat is the best they’ve ever tasted.”

Grass Finishing Steers at Stemple Creek Ranch

At harvest, the finished animals are trucked to a USDA-certified processing facility. Stemple Creek’s animal welfare practices are audited and certified through the Global Animal Partnership (GAP) program. Loren says their Level 4 certification for their beef reflects their commitment to the respect and care their animals receive.

After harvest, the meat is transported to Stemple Creek Ranch’s retail packing partners for cutting and packaging. Some meat is broken into larger or sub-primal cuts for restaurants, specialty butchers and grocery market segments. Some of the meat is processed into smaller cuts for direct-to-consumer market outlets, including their online store and farmers’ markets.

They went from sales of about $1 million in the first year to $8 million in 2022. “If you build it, they will come,” Loren says. “And if you're passionate about what you do, follow your passion, and good things will happen.” At startup, Stemple Creek’s only employees were Loren and Lisa. They now have 15 employees. They now sell at two farmer’s markets and ship direct to consumers, which generates approximately $1.5 million. The other $6.5 million is generated in annual sales to grocery stores, restaurants and butcher shops.

Left: One of the restaurants Stemple Creek sells to

While the couple still maintains a presence on Facebook they are more active now on Instagram. They also use the social media platform TikTok, even though Loren admitted he has yet to determine if they will generate sales from that platform. “We’re getting a lot of love from it, and it seems some regenerative producers are using TikTok to get the word out,” Loren says. “They’re pretty good with it, so we’re going to try it out.”

Stemple Creek Ranch ships meat to all 50 states, with orders typically arriving at their destinations within 1-2 days of leaving their shipping facility. All meat is shipped frozen to provide optimal storage in transit. When an order is received, a team member pulls the ordered cuts from their warehouse freezer, places the orders in crates, and brings them to the packing station. Each order is boxed and packed with dry ice, with additional ice added if the packer feels additional protection is needed in case of an unexpected delay or because of the distance in transit.

The Transition to Regenerative Agriculture

Loren says he and Lisa have been producing regeneratively since before it was called regenerative. “We started focusing on soil health and biodiversity, which are regenerative practices,” he says. “We kind of fell into it. We didn't say, ‘Oh, we want to be regenerative farmers.’ We just looked at what we were doing and realized we were checking all these boxes.”

The shift to regenerative production strategies began when Loren realized that they had to start grazing differently because they didn’t have enough land for the grazing they wanted to achieve. The couple began adaptive grazing, planted more forbs and even used a rip seeder to help break up old compaction layers in the soil. A primary focus of their effort was to get perennial grasses established instead of relying strictly on annuals. Forbs, such as chicory and plantain, were seeded to help establish greater diversity and better phytonutrient content in the diet of the animals. They fenced off the riparian areas and planted trees and hedges to slow erosion and increase carbon sequestration.

The Staff at Stemple Creek Ranch (not everyone is pictured)

As they implemented the more adaptive grazing strategies, Loren says things were progressing well until they ran out of feed one day. Loren says he realized he was misallocating his grazing resources, particularly for his cowherd, using their better pastures for mama cows. In response to this revelation, they moved their cows off the home ranch to other ranches. Loren also sold some cows to a neighbor and bought bulls for that neighbor, allowing them to maintain production using the same genetics. Working with a select group of like-minded ranchers has facilitated growth in Stemple Creek Ranch’s production while honoring a management philosophy of supporting soil health while producing high-quality animal proteins.

Stemple Creek Ranch was one of three test ranches in their county participating in the Marin Carbon Project, a 10-year study that began in 2014 to determine the effects of carbon retention on soil health. Initial data show Stemple Creek Ranch sequesters between 1,000-3,000 pounds of carbon per acre annually with current management practices. The study demonstrates that as more carbon is sequestered through photosynthesis with their increasingly diverse flora more nutrients and water are retained in the soil, contributing to increased forage productivity in their fields. For every 1% of carbon sequestered into the ground, Loren says they store from 18,000-25,000 gallons of water per acre. By adaptively grazing and applying compost to the pastures, they are extracting and sequestering more CO2 out of the atmosphere than by conventional ranching. In addition, ranching regeneratively has proven to be better for the ranch and the cattle and has significantly improved resiliency.

Stemple Creek Ranch also is active with the Marin Agricultural Land Trust (MALT), a land trust developed to protect agricultural land in Marin County from mounting development pressures. Part of the ranch is protected with a conservation easement wherein MALT purchases development rights from landowners, extending them in perpetuity. While the land remains in the rancher’s ownership, the legal agreement formed with MALT guarantees the land’s ongoing agricultural use. Loren’s father served on MALT’s founding board of directors, Loren served on the board for about a decade and Lisa, currently serves on the board.

Loren’s passion for regenerative agriculture ramped up to a new level after attending his first Soil Health Academy in 2018 at Chico State University where he met Allen Williams, Ph.D., (one of the founders of the Grassfed Exchange and founding partner of SHA and Understanding Ag, LLC) and Gabe Brown (also a founding partner of SHA and Understanding Ag, LLC). Shortly thereafter, he began watching YouTube videos that featured the two. “Now I’m a disciple of Allen, Gabe, and Understanding Ag,” Loren says. “I think we are making good progress. I’ve realized that what we're doing is special, we're getting good results, and it's fun. And the consumers get to vote with their dollars, and they're voting for what they want. And the meat tastes fantastic.”

Loren and Guests Touring the Ranch

Loren is also a self-described disciple of Ranching for Profit, whose training programs helped dramatically change their lives before Understanding Ag came into the picture. “Ranching for Profit gave me the confidence to quit my day job and go full bore into our new ranching business,” he says. “Being part of the executive link, where I had five other ranchers looking at my business, and where I'd look at their business, we'd hold each other accountable. That was really awesome. And I learned a lot from that.” Applying what they learned from Ranching for Profit, Loren and Lisa began making decisions based on enterprise analysis, realizing that it was a much better way to manage, based on the financial performance of individual enterprises, and “not just have a checkbook and when there's no money left in it, you can't pay yourself.”

Current regenerative practices include pulse grazing (adaptive grazing) and cover cropping with ryegrass, clover, plantain, and brassicas, which are planted using a no-till drill or by broadcasting. The perennial grasses are able to penetrate deeply into their compacted soils, building aggregates while extracting nutrients.

Using adaptive grazing strategies, they move their cattle frequently, which contributes to weed control. The pastures are given adequate rest, which encourages healthy forage growth and diversity. During the peak of their Mediterranean climate growing season, they can return to graze pastures as often as 21-22 days, but otherwise, they plan on 60-180 days of pasture rest.

Making daily moves with the finishing heifers

Loren said they make their own compost from wood chips and other plant organic matter, which they spread on their pastures to increase soil organic matter. A thin application of their compost helps sequester carbon for several years. They also use worm-casting “tea,” poultry manure from neighboring farms, and a spray-on blend of micro-nutrient rich seawater, liquid kelp, humate, and fish oil, to boost available minerals and nutrients to enrich their soils’ microbiome.

Loren reports that their forages now stay green longer into the drought season and he is especially encouraged that their efforts to protect and enhance native ecosystems have attracted over 50 species of migratory birds. “It has been immensely gratifying to see the vast changes we’ve made in a relatively short period and we can’t wait to see what else we can accomplish,” he says.

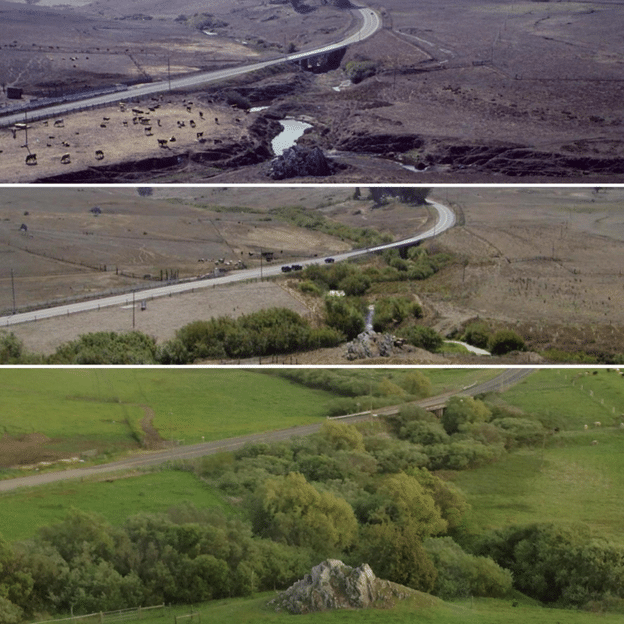

The progression at Stemple Creek Ranch has been dramatic. This series of old photos

documents that progression. Loren and his family are ecstatic with the changes made to the

landscape and ecology.

Challenges and Problems

The geographic location of the ranch means Loren and Lisa must manage through seasonal droughts. Half the year, there is ample rainfall (often too much) and the other half is dry. Loren says 2-3 inches of moisture in October to start the growing season, plus another 2-3 inches in May to extend forage production into summer is ideal. Their goal for their soil is for it to be able to infiltrate water like a sponge so the water will be available for as long as possible, ultimately providing forage for their livestock year-round.

Stemple Creek doesn’t use an extensive operating line of credit, nor do they have any investors. “It's just us, and we just built it slowly and surely,” Loren says. “I think we're getting good results, but until we stop growing, we don't pay ourselves much. Like other operations, we pay ourselves a salary.”

Stemple Creek Ranch’s motto is, “Go slow to go fast,” focusing on moving up the learning curve slowly to test opportunities and strategies, then taking those that work to scale.

Loren now has millions of dollars invested into their operation. The couple is now asking, “What do we do next? What are the next steps? Do we continue to grow? Or should we stop growing and pay ourselves more?” Other possibilities for the ranch include adding a partner or finding an investor. “We don't really know,” Loren says. “ This is a big thing for many small brands like ours: What do we want it to look like as we move into the future?”

In the beginning, Loren and Lisa wanted to sell everything they raised. “We did that. Then we wanted it to be financially viable, to provide a livelihood for me, my wife, and our family and we did that,” he says. Now they are pondering what’s next. Loren doesn’t want to be doing a bunch of jobs but rather wants to focus on financial decision-making.

What really excites Loren is regenerating the soil, establishing perennial plants, and raising high-quality cattle. “Having diverse pastures almost gets me more excited than having a choice carcass. It's pretty cool,” he says. As an example, Loren described a field they are working to reclaim now. This field had been leased to a tenant for 12 years to grow water buffalo–a field he describes as depleted and abused from poor grazing management–basically bare soil.

Water Buffalo Pastures in depleted condition

To rehabilitate the pasture, Loren started by spreading cow manure, because it’s free and adds some fertility. In the winter of 2022-23, Loren disked the soil lightly and seeded winter cover crop species. He knows the process will take time, but Loren is committed to totally regenerating that field and is excited to monitor and record the healing progress over time.

Loren says his adventure into regenerative agriculture is part of a “grand experiment” the results of which, thus far, have been very encouraging. Their focus has been on learning how to best partner with Mother Nature, explicitly giving more to the soil than they extract, which is a philosophy that is proving to be the best way to ensure their multi-enterprise animal protein operation is sustainable into the future. “It’s better for our land. It’s better for our animals. It’s better for the consumer,” he says.

Agri-Tourism and Farm Events

Loren and Lisa have developed a very robust event and farm stay business. This includes three on-ranch Airbnb properties. These properties originated from ranch buildings that have been completely renovated for guest stays.

The Schoolhouse Guest House

The Cabin

The Writers Cottage

The main barn has been converted into an event center that hosts weddings, family reunions, workshops, dinners,and many other events. It is equipped with a full commercial kitchen and has a large open space to accommodate different sized crowds.

Main barn set up for a wedding

Wedding Party

Many types of private events are hosted at the farm due to the rural ranch setting and the nice facilities. These range from corporate events, to family reunions, to small company gatherings.

Other events hosted by the ranch include the annual Stemple Creek Farm Dinners and Ranch Tours and workshops.

Various events at the farm

Loren realized early on that the best way to sell good food was to put it in people’s mouths. To effectively accomplish that getting people to the ranch on a routine basis is crucial. By requiring that all events use Stemple Creek proteins, Loren is able to expose a large number of people to their regeneratively-raised foods each year. It is also imperative that people see exactly how their food is raised. Getting them out to the ranch allows them to show folks how the livestock are managed and what they are eating. This instills a high level of confidence with their customer and creates transparency.

Ranch Workshop

Annual Farm Dinner

Awards and Honors

The ranch has received numerous awards and certifications through the years. In 2002 Loren’s father, Al Poncia, was the recipient of the USDA NRCS’s most prestigious award, the NRCS Excellence in Conservation award.

In 2013, Loren was the recipient of the J.W. Jamison Perpetual Trophy for being named outstanding North Bay Rancher of the Year.

Other awards and certifications include:

The Marin County Farm Bureau Lifetime Achievement Award honoring Al Poncia for 50+ years of service to agriculture. Al was recognized as an early pioneer in conservation and environmental stewardship.

Stemple Creek Ranch Global Animal Partnership (GAP) status of Level 4 Certification (GAP 4) fr animal welfare and humane care.

The Marin Organic Certified Agriculture certification. Stemple Creek has been certified organic since 2008.

Recognized in the Grown Local Marin County and Go Local Sonoma County programs. This effort supports locally grown and raised food products.

The Audubon Conservation Ranching (ACR) program Bird Friendly Grazing certification. This certification awards those who are regeneratively grazing to support ground nesting birds, song birds and migratory birds.

For additional information, please visit:

https://www.marincarbonproject.org/

Note: Some of the content presented in this case study was sourced from selected Stemple Creek Ranch newsletters.