August Horstmann began his farming career following the scholarly prescriptions he was taught by his animal science professors at the University of Missouri (Mizzou).

Following those prescriptions nearly ended his full-time farming dream.

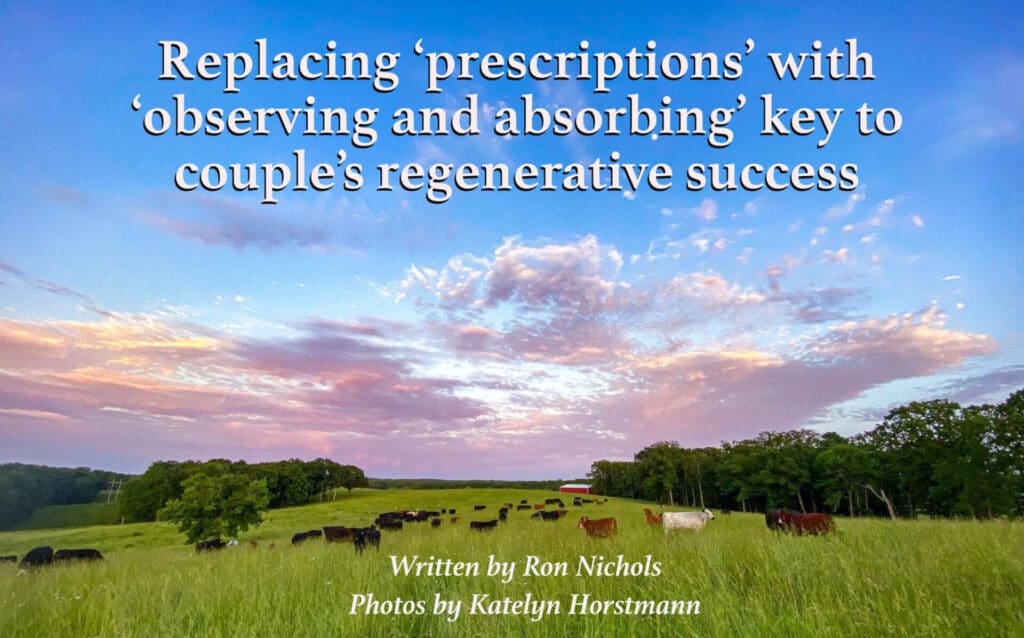

On his family’s 1,000-acre farm in Owensville, Missouri, the then 19-year-old Horstmann used registered bulls for breeding, fed his herd grain, included antibiotics in his mineral supplements “just because,” baled hay and selected breeds based more on tradition, rather than on the animals’ suitability for the environment and other genetic traits.

In late 2015, after graduating from college, Horstmann was feeding his 65 replacement heifers, along with the bulls, up to 300 pounds of protein a day. After calving the following spring, his herd grew to 100 and Horstmann’s feed and input costs were straining his finances.

“I realized I had to get an off-farm, full-time job,” Horstmann, now 26, says. “I made it three months from the time I graduated—thinking I was going to be a full-time farmer—to having to get an off-farm job.”

Then he took a job with a local farm equipment dealer as a “parts guy” to gird his personal finances. “Early in the summer of 2016, I bounced one check on my farm account, which I paid from my personal account,” he says. “I told myself ‘I’m never going to do that again. I’m never going to fund my farm with my personal job.’”

Throughout that summer, Horstmann purchased feed on credit, promising to pay the feed company when he sold his calves in the fall.

“For two months in the summer of 2016, I only had $10 in my farm account,” he says. “Pretty crazy.”

Later that fall, Horstmann says he paid up all of his bills and cut back on his feed. And then he married his wife, Katelyn.

“The farm was requiring all of my attention,” he says. “Katelyn and I didn’t even go on a honeymoon because we had to wean the calves right at the prescribed 205 days after birth. Because everybody knows if you’re going to be profitable, you follow what you learned, you follow the prescription.”

In April of 2017, Horstmann took a new job with a local soil and water conservation district as a technician. His first day on that job set in motion a series of events that changed the trajectory of his farming operation and his future.

“That day, a co-worker handed me a post-it note with four names on it,” Horstmann says. “Those names were Ray Archuleta, Gabe Brown, Greg Judy and Dr. Allen Williams. My co-worker said, ‘Just search these guys on YouTube and watch.’”

“One of the first videos I watched was Gabe Brown’s presentation on nearly going broke with his farm, and then I watched Allen and Ray talking about soil and cattle, working with nature, and managing the land instead of buying land,” Horstmann says. “That got me hooked.”

So, after years of following the conventional agriculture prescription of feed, fertilizers, vaccinations and de-wormers, Horstmann says, “we just cold-turkey’d it all. I was like, ‘I can get behind this.’ We even went so far as to sell all of our haying equipment.”

But the abrupt transition was not without its pitfalls, Horstmann says. “We had our share of wrecks, I will tell you that.”

After the Horstmanns quit feeding their bulls and steers and stopped feeding supplements to their cows, 25 percent of his cows were “open,” or not pregnant the following fall—a situation Horstmann attributes to cows that were too reliant upon supplemental feed and inputs.

“We culled those cows and sold them for $461 each,” he says. “Not a great price, but we didn’t have to carry them over the winter.”

Subsequently, the Horstmanns began selecting breeding stock for characteristics that would be a better fit within the context of their operation. “When I would buy a bull, I would ask, ‘Which bull stood at the feeder the least?’ And then I’d take that one.”

In the ensuing years they enrolled their farm in both state and federal conservation programs, which helped finance infrastructure improvements like high-tensile cross fencing, watering facilities and more than tripled the number of paddocks (from 15 to 46)—all of which further enabled their adaptive grazing plan.

“YouTube, YouTube, YouTube”

Horstmann originally enrolled in the animal science program at Mizzou to become a veterinarian, but soon realized it wasn’t a good fit.

“I was terrible at school,” he says.

Still, he continued his studies to earn his degree. But unlike many of his college mates who spent their weekends absorbed in the revelries of campus parties, Horstmann spent all but one of his weekends during his four years attending Mizzou back on the family farm.

Like many college graduates, Horstmann’s introduction to regenerative agriculture began after he had his degree in hand—via YouTube videos featuring pioneering farmers like Brown, Williams and Archuleta.

“I put a lot of faith in those YouTube videos,” Horstmann says, looking back. “I just took a shot in the dark. I thought, ‘This is our last-chance hail Mary or whatever you want to call it, or we’ll be day-job people and have to farm on the side.’”

His stint with the soil and water conservation district provided Horstmann with ample opportunities for additional learning, including attending soil health and grazing conferences and field days. “Anything within a three-hour drive, I would try to get approval to attend,” he says.

The more he learned, Horstmann says, “The more it made sense to work with nature, not against it.”

Comparing and contrasting

Horstmann’s work as the farm manager of a conventional register Angus cattle operation afforded him with a unique opportunity to compare and contrast the input-intensive conventional operation with that of his own.

“Seeing the money that was being spent on feed compared to my operation and how the genetics of the cows at the conventional operation were getting bigger while mine were getting smaller was eye opening,” he says. “Seeing the comparisons made me push harder to step even further out of the box and push my cows harder to be better grazers.”

Horstmann has taken the regenerative lessons he’s learned with him to his latest job of managing another cattle operation. (He says his previous job with a registered beef operation’s conventional approach “Wasn’t a good fit.”) By more effectively managing the forage resources on that farm, Horstmann has been able to reduce hay feeding from 200 bales last year to just 20 this year.

‘I’m absorbing.’

While moving his own cattle, Horstmann pays special attention to animal behavior—what his cows are eating, their habits and when they give birth.

“I do this at work, too,” he says. “I absorb what not to do most of the time and can still use that information in my personal farming decisions.”

For example, Horstmann asks, “Why are cows calving in the winter? Well, they’re calving in the winter because their bulls don’t want to work in the hot summer. Why would you risk your cow and your calf because your bull doesn’t want to work? So why not select bulls that will work in the hot summer?”

So, since the fall breeding season of 2018, Horstmann has been using South Poll bulls only.

And by implementing an adaptive grazing system, the Horstmanns are seeing the return of rest and forage growth, as well as extending their grazing periods further into the winter. Cattle traveling as they graze has helped eliminate the need to address foot-rot or fescue related issues—requiring no treatment for those diseases whatsoever in the past two years.

“I was just happy with the results. I didn’t really put it all together until I realized we stopped fertilizing and implementing adaptive grazing that our forage was becoming more nutrient dense. Connecting all the dots to soil health happened when I attended a couple of grazing field days in August of 2019 and started working with David Kleinschmidt and Allen Williams, consultants with Understanding Ag, during a Pasture Project workshop.”

In October of 2019, Horstmann attended a Soil Health Academy hosted by Ray Archuleta in Missouri, where he met Shane New and Gabe Brown, further expanding his understanding of the relationship between healthy soil, healthy plants and healthy animals.

After working with Understanding Ag consultant Shane New for just one day this past summer, he says he also learned important lessons on what to look for when culling: “Always know the bottom 20 percent,” he says.

Then he went back home and immediately started putting the regenerative lessons he’d learn to work—not the least of which was learning to observe.

“I was putting high-density, low-density, ultra-high-density practices to work—getting our cattle to graze things I just never would have imagined getting a cow to eat,” he says. “I could talk four hours on just what I’ve seen in the past year. It just blows my mind.”

When it comes to his pastured-pig breed selection and stocking density, Horstmann takes an “observe and absorb” approach to that endeavor, as well.

“I’m currently on my second batch of pastured pigs and I don’t even know what breed they are,” he says. And when it comes to stocking density, “With all of my animals, I do it all by sight, by trial and error,” Horstmann says. “If I don’t give them enough forage one day, I note it and make it bigger the next.”

The same goes for the Horstmann’s current 275 head cattle herd. “I do it all by sight, by observation.”

Horstmann says “absorbing” means putting the knowledge gained through thoughtful observation to work to ensure everything observed, good or bad, informs his next series of decisions.

“It comes down to understanding what you observe and how to apply it,” he says. “Often, when Katelyn calls to ask me what I’m doing, I tell her, ‘I’m absorbing.”

“When the Farm Bureau and Cattleman’s Association won’t talk to you, and you only get talked about, that’s a complement to a regenerative farmer. You know you’re doing it right.” – August Horstmann

The bottom 20 percent principle

After attending the SHA school in Missouri and meeting Brown and Williams, and learning from New, culling the least productive, most problematic cattle became a major focus for Horstmann.

By concentrating on the top 80 percent, he can now use his forage resources to feed the most profitable animals.

“When you start doing that, you’re feeding your better animals instead of just culling your older cows,” he says. “In college, we were taught to cull the older cows, but some of your older cows may be your best. This summer we rode around and wrote down the bottom 20 percent that have long hair, lots of flies or both and we sorted those off this winter. When we pregnancy checked those cows this winter, almost all of them were open,” he says. “They just didn’t work for our operation.”

In May of 2018, the Horstmanns also consolidated the farm’s four herds into one, providing longer periods of rest for individual paddocks. After observing some of the South Poll cattle he was custom grazing, Horstmann observed the breed “slicked off really fast with short, fine, oily hair”—with much less fly pressure. Further observation noted the black Angus breed cattle were staying in the shade longer, grazing for shorter periods of time, compared to the red South Poll cattle that were coming out of the shade earlier and grazing for longer periods of time.

These traits led Horstmann to select South Poll bulls to cross breed with Angus cows. The bulls’ offspring, though black in color, retained the positive traits of the South Poll cattle he had observed.

Shortly after discontinuing the use of wormers, fly control and antibiotics , Horstmann also observed that cow birds began returning by the hundreds and that there were “dragonflies like you have never seen before.”

“The number of insects you see in our fields now is out of this world,” he says. “Last year we had so many spiders in our fields it looked like someone had spun cotton candy around our cows’ heads. We loved seeing them because every time a cow would lower its head to graze, the face flies would get stuck in the spider webs.”

Stacking enterprises, direct-to-consumer marketing

Horstmann’s “side job” of managing a registered Angus cattle operation located 25 miles from his farm was significantly limiting his ability to care for his own, so in the spring of 2018, Katelyn quit her day job as a veterinarian technician and took over the day-to-day operations at the Horstmann farm. In addition to the daily tasks of moving cattle and calving, she began developing the farm’s social media presence—which proved to be an important marketing tool when the couple’s meat business blossomed.

“It has always been our dream for both of us to be able to work full time on the farm,” Katelyn says. “However, I never imagined that I would be the one doing all the day-to-day work during the week, feeding and moving all of the animals, and managing all of the social media platforms.”

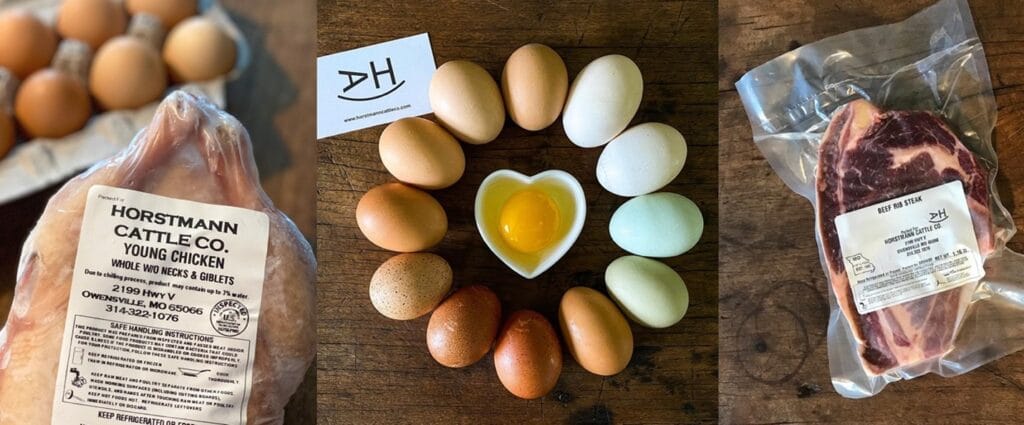

About two years later, COVID-19 provided the catalyst for the Horstmanns to jump into that meat business. As grocery shelves emptied from shortages and consumers became increasingly cognizant of the need to eat healthy, nutrient-dense food, the pandemic became a marketing opportunity.

“We made a ton of butcher appointments for our cattle—just picking dates and guessing at the number of cattle to schedule,” he says. “Then we jumped out on a limb, bought some pigs and scaled up our layer operation.” he says.

This decision was informed by an important lesson he learned during his time at the Soil Health Academy: Integrating multiple enterprises per acres with pigs, chickens, broilers, spring and fall calvers, stockers, grass-finished beef, and other animals and enterprises.

“It just makes sense to do it because different animals consume different forages and provide different disturbances per acre,” Horstmann says. “We plan on having bee colonies and hives in the near future.”

Having developed the Horstmann Cattle Company Facebook page a year before, Katelyn frequently posted photos and happenings around the farm, which began attracting visitors who were looking to purchase pasture-raised beef. The Horstmanns asked page visitors to subscribe to their e-mail list, which they then used to notify customers of product availability, offering those products on a “first-order, first-serve” basis.

Every other Saturday, the couple would make a 200-mile round trip to deliver those products directly to their St. Louis-area customers’ doors.

Why not cultivate a more local clientele?

“Everybody in Owensville thinks I’m a whack-job,” Horstmann says with a chuckle. “No one here buys any beef from us.”

Horstmann says their product pricing also reflects the value their customers place on health and the environmental benefits of their regeneratively grown products, which is another reason the Horstmann’s market niche necessarily extends beyond their immediate locale.

“At $7.50 a pound for our ground beef, we’re sourcing customers who are increasingly making the connection between healthy soil, healthy plants, healthy animals, more nutrient-dense animal proteins,” he says. That premium price point also allows the Horstmanns to provide door-to-door service.

It also provides a business model that is consistent with their stewardship ethic.

“I love being able to raise animals in a manner that is good for the environment, the animals themselves, and our customers— healthy soil, healthy plants, healthy animals, healthy food for our customers,” Katelyn says.

Since their deliveries began in the spring of 2020, the couple has consistently processed two steers a month, helping them keep pace with sales. As a result, the farm is becoming more and more profitable with most of those profits going into infrastructure improvements, including watering facilities, fencing and practical education, like that provided by the Soil Health Academy.

Perhaps as importantly, improved profitability has the young couple considering taking that honeymoon/vacation get-away they were unable to experience when they were first married.

“Thanks to adaptive grazing, we can actually go places now,” Horstmann says, “because the farm doesn’t need us all the time.”

As they look to the future, the Horstmanns want to add even more diversity to their farm by adding fruit trees, vegetables and more animal species, “starting with bees and sheep,” Katelyn says.

Ultimately, the couple hopes their regenerative journey will lead them to an even brighter future. “I would love to be able to build a business that could be passed down from generation to generation,” she says.