Seven Sons, LLC, Roanoke, Indiana

Introduction:

Seven Sons, LLC, is located near Roanoke, IN in Allen County. The name of the farm comes honestly as there are Seven Sons born to Lee and Beth Hitzfield, the patriarch and matriarch of the family. The seven sons, in order from oldest to youngest are: Blake, Blaine, Brice, Brock, Brooks, Bruce, and Brandt. The farm is a second-generation enterprise, with all seven sons active in the operation. The grandchildren are the foundation of the third generation.

Seven Sons, LLC operates on 550 acres of arable land near the larger city of Fort Wayne, IN.

History

Lee Hitzfield was not a farmer by birth and did not grow up on a farm. His family was in the construction business and Lee was originally an excavator and bulldozer operator. In the 1970’s he bought a small “hobby” farm and then in 1983 he and his wife, Beith, purchased the original 20 acres that was to become the farm they operate today.

The original 20 acres included a 150-sow, farrow-to-finish hog operation. The owners had retired and wanted to move to Florida so Lee bought the hog operation as a working farm. It was a conventional confinement hog farm that produced pigs sold into the commodity market. At the time, Lee knew nothing about raising and finishing hogs but the owner who sold him the farm agreed to take some time to train Lee on the finer points of confinement-hog farming. In addition, Lee bought a subscription to a Purdue University manual on raising pigs and admits he followed that manual to the letter. He also stated that they had IBP bumper stickers on their trucks (IBP was one of large meat packers at that time).

The Days of Commercial Pig Production

Lee and Beth needed more than the income from the confinement hog operation, so they leased about 1000 acres of row crop land from 20 different landlords. Managing that many landowners is, in itself, a big task. Since Lee had never farmed before, he sought information from conventional sources including Purdue University, the state Extension Service, and “the normal crowd of seed, fertilizer, and chemical salespeople.”

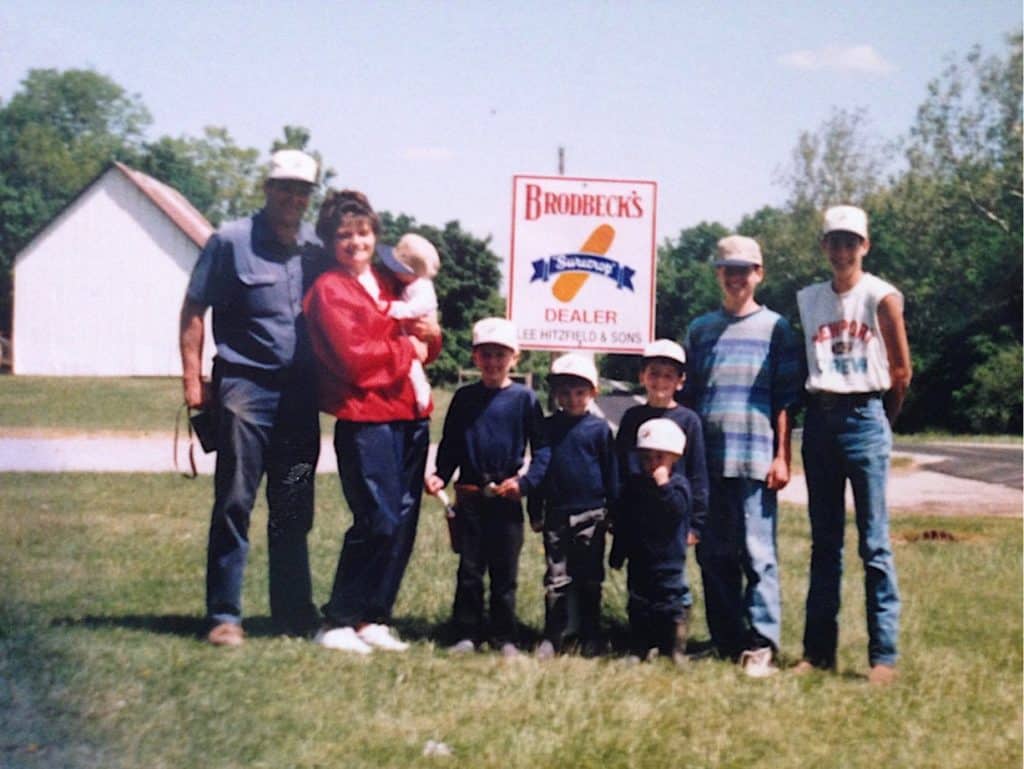

The Old Days of Conventional Farming. Lee and Beth with the Seven Boys.

Cropping Practices:

The row cropping operation was heavily reliant on full tillage, synthetic fertilizer and chemical use. Lee was farming exactly how he was directed by the university and industry folks from whom he sought advice. Lee and his oldest sons proudly wore the seed, fertilizer, chemical, and equipment company hats and jackets. They grew corn, soybeans, and small grains (primarily wheat) in soils that were barely over 1% soil organic matter (SOM), which is 3-4 times less than what was present in the area soils originally. In just under 200 years of cultivation, farmers had reduced the soil organic matter significantly, going from soils that would have been at least 8% SOM to soils under 2% SOM.

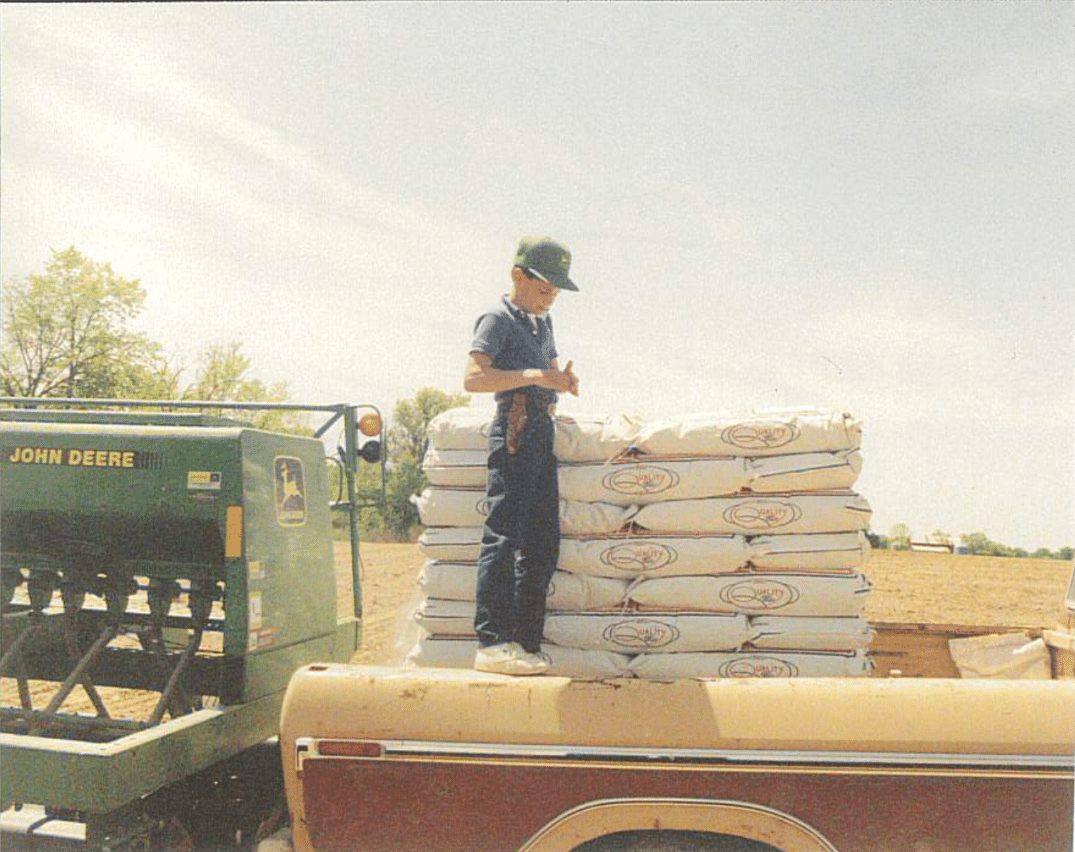

Typical tillage practices consisted of chisel plowing, moldboard plowing, and disking. In a typical cropping year, Lee and the older boys would plow all through the night during the spring planting season, making multiple passes over each field. He purchased deep tillage equipment for every tractor so three could be running at all times. These multiple field passes were burning fuel, labor, and were generating depreciation and maintenance costs. Additionally, the high degree of tillage was doing significant damage to the SOM, to soil carbon, and to the soil biology. Lee and his sons did not know this at the time and simply believed they were farming the way you were supposed to.

The farm was dependent on heavy synthetic fertilizer and chemical use. At that point in Lee’s journey, he would scoff at anyone who mentioned “organic” or “natural,” thinking it was all “a bunch of hooey” and favored the use of herbicides and genetically modified seed. In so doing, Lee was inflicting heavy damage to the soil biology and physical structure without knowing it. He was told repeatedly “You have to farm this way to feed the world.”

In the late 1990’s Lee bought a John Deere 750 no-till drill. He had seen a picture of the openers on the drill and thought the planter might work for him, so he gave it a try for a while—then called it quits. (It’s important to note Lee was not implementing any other soil health principles at that time.) He was one of the very few who had a no-till drill in Indiana during that time period, but he was trying to use it to plant into bare soil as he was not planting any cover crops. He got so disgusted with the efforts that he came to refer to “no-till” as “no yield.” Lee experienced what many farmers do when they try to switch to no-till farming. Their soils have been so pulverized, compacted and degraded by the frequent tillage and chemical use that they are unsuitable for no-till. No-till works far better with other regenerative practices to help prepare the soil and re-establish some semblance of soil biology and aggregation.

Conventional Row Crop Farming in the early days

Getting the Boys Involved

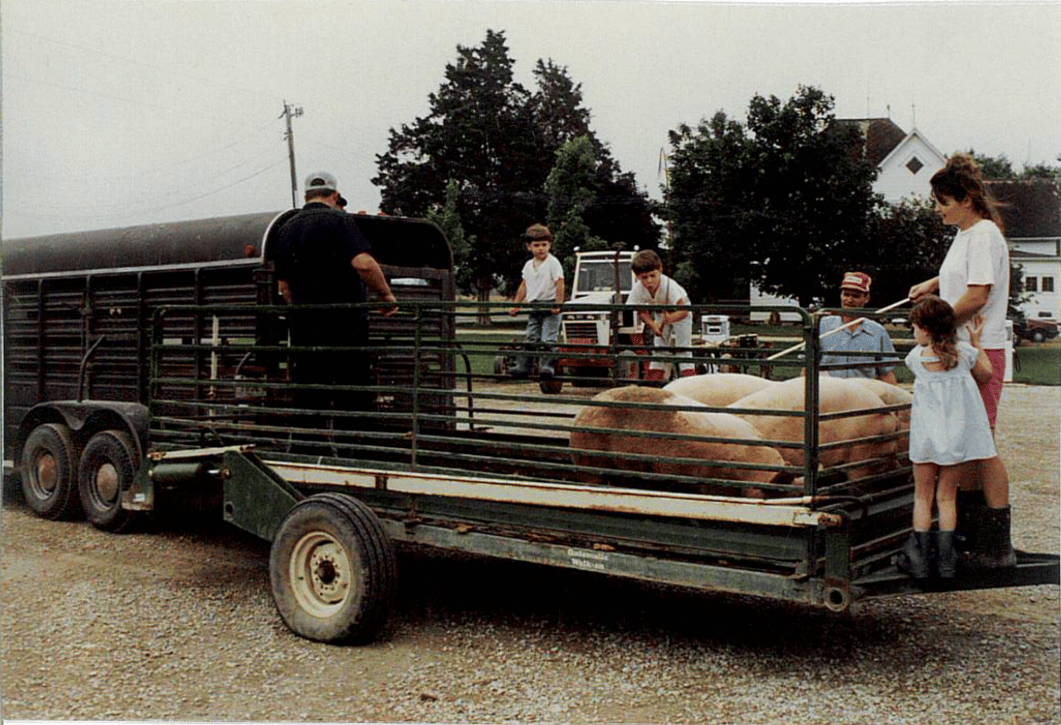

While the family still had the confinement hog operation, Lee encouraged the two oldest boys, Blake and Blaine, to buy and raise young pigs. They were already helping with the hog enterprise and this was a way to further incentivize them and teach them business skills.

Lee admits that they had 12 good years in the confinement hog business. The pigs paid the bills and made everything work financially, leaving the family convinced that commodity agriculture worked. This is typical of most farmers. When things are working financially, there is no real incentive to make changes.

The Beginning of the Transition

In 1991, Lee met a mentor named Ray Smith. Ray was way ahead of his time in practicing what we know today as regenerative agriculture and was a vocal advocate of those practices. Ray took Lee under his wing and convinced him to apply some high-calcium lime to his soils to correct low-pH issues and to cut his chemical use by 25%. Ray also recommended Lee use lower plant populations in his corn and soybeans.

In 1992, Beth gave birth to their third son, Brice, but within three weeks of delivery she became very ill. Beth had a hard time taking care of Brice, was very exhausted, and often times bedridden. Neither Beth nor Lee knew what was happening, nor did they understand why her health was deteriorating so fast. They went to a number of doctors and specialists who were unable to pinpoint the cause of her health problems. She became so ill that it was almost impossible for her to function at all.

With three sons to care for, heading into the heart of planting season with 1000 acres to plant and 150 sows and their pigs to take care of, Lee recalls this time period as “overwhelming.”

Enter Ray Smith again. Ray had worked closely for a number of years with Dr. Carey Reams and was an agronomist working for a soil testing lab. Ray had no formal medical training but he understood how biological systems worked.

Dr. Reams had a deep understanding of many scientific disciplines and understood system functioning. Years earlier, Dr. Reams had a number of interactions with Albert Einstein.

Medical tests revealed that Beth had rheumatoid arthritis and that the inflammation had spread rapidly through her body. Doctors told her that in a matter of two years she would need a hip replacement and be wheelchair bound. They also told her she would never survive another pregnancy.

Picture of Ray Smith (second from left) with Lee (far left) and Blake (far right)

Ray Smith, with his understanding of biological and physiological systems, explained to Lee and Beth how soil, plant, animal and human health are inextricably linked. Ray hypothesized that Beth had mineral deficiencies and an acidic pH body condition, as a result of her pregnancy with Brice, which he believed had pulled a lot of minerals out of Beth’s body, weakening her immune system.

Ray provided Beth with a recipe to balance her body’s pH and, with sound nutritional advice, in a matter of days, Beth was back on her feet and feeling completely normal. Her energy level returned and she felt wonderful, eventually giving birth to four more boys.

Throughout this period, Lee and Beth learned about the value of nutrient-dense food. They started using a refractometer to test produce in the grocery store and only purchased fruit and vegetables with higher brix values. Interestingly, they often found that conventional produce had a higher brix value than organic produce. Lee wondered why and concluded that it must be all the tillage and cultivation practices commonly used in an organic operation. Excess tillage had robbed the soils of their microbial populations and therefore their ability to produce nutrient-dense foods, despite being certified organic. That started a change in the way Lee thought about things, including his years-long heavy tillage use—just like many of the organic farmers.

During Beth’s journey to recovery, Blake and Blaine say they distinctly remember standing at the juicer day after day making fresh vegetable and fruit smoothies for their mother, which she would drink throughout the day. Simply changing her nutritional profile transformed Beth’s health. At times she drank so much vegetable juice that her complexion turned orange from the beta-carotene.

This incident was not only the turning point in Beth’s health, but it became the turning point in Lee’s mind regarding his farming and food-producing methods. Lee now realized that he had been a farmer of commodities, not a farmer of nutrient-dense foods and he was determined to change that. This is not something that is easy for farmers to admit. Most farm all of their lives believing they are producing healthy, nutrient dense foods and it’s a tough pill to swallow when they realize that healthy food must be derived from healthy soils. If the soils are depleted of SOM and the mineral cycle is hampered, then the vegetables, grains and proteins they are producing are deprived as well.

In 1995, Lee sold the sows and got out of the confinement hog business. He hit the market just right as hog prices were at a historic high, right before one of the biggest drops in hog prices in history. He received top dollar for his sows right before the downturn, getting out of the business before they would be required to remodel their swine facilities. Lee admits that he had lost his belief in the commodity system and being able to sell out at this critical point in time was “a huge blessing.”

During this time period, Lee decided that he either had to get out of farming altogether or make wholesale changes in how he was farming. Ray Smith had introduced Lee to Stockman GrassFarmer magazine and Lee became a voracious reader of the articles. He would read articles by regenerative pioneers like Joel Salatin and Allan Nation, reading these articles to the boys as bedtime stories.

Rather than financially motivated, Lee’s regenerative journey was based on the basic concepts of human health. Because Lee forgot the financial component, he says, “The next ten years were the toughest yet.”

The Middle Years

When Lee transitioned to regenerative agriculture, he switched completely to livestock but did not have the knowledge base needed to understand exactly how to make this work. The family hit a wall in year three of the switch to livestock and they stayed stuck at that wall for about 10 years, coming close on several occasions to losing the farm. Lee actually took an off-farm job just to pay the bills, while the older boys were “working their butts off for very little compensation.”

Blake and Blaine had saved some money from their years in the confinement hog business—money they kept in jars. When Blaine was about 14 years old, they were putting up a lot of fencing for the livestock and Lee had to ask the boys for the cash in their jars just to pay for it. Blaine remembers this incident distinctly because he had the good fortune to initially pick out a far more productive sow than his brother Blake, when they were still in the hog business. Blaine had earned more in the hog business than Blake and contributed his cash to help the family in this time of need.

Through the late 1990’s Lee started taking row crop ground out of production and putting it into perennial pasture. This was fortuitous because he later lost 260 acres of their leased land in a single year to housing and industrial developments. They were now down to 700 acres and decided to complete the move to pasture and hay production.

In 1997 Lee began leveraging borrowed money to buy cattle, traveling to sale barns in Cuba, MO and Vienna, MO to purchase the cheapest cow/calf pairs that came through the sales ring. Most of those buys were “roper” cattle (less-desirable breeds of Corriente influence with horns previously used in roping practice or competition). They could buy those types of cattle for $30-$40/cwt and lowered their travel lodging cost even further by sleeping in their truck or the cattle trailer the evening before the sale was to begin.

Because these cattle were roping-type cattle, that meant they did not have the genetics for producing a high-quality, well-marbled beef. Coupled with the fact the Hitzfields really did not understand direct marketing, proper finishing, or cattle genetics for grass-based beef production, and they ended up with a product that was very lean and somewhat tough. Lee’s primary goal was producing foods that were free of chemicals and added growth hormones.

They were still growing some non-GMO corn at that time and feeding the grain to the livestock for final finishing. Lee remembers testing the protein level on his corn and it was a very low 4.7%. He asked several seed suppliers and crop consultants about that, and they told him most commodity corn was testing in the 4-6% protein range, but when Lee focused more on the soil health principles first taught to him by Ray Smith, he was able to increase the protein levels in his corn to 10%. This improvement is experienced by many regenerative farmers, a consequence of improved soil biology, resulting in better nutrient profiles in the resultant crops.

Exiting Row Cropping

Once again, Ray Smith was instrumental in encouraging change. About every two weeks he would visit the farm and shake his head at all the farming equipment Lee owned. Ray repeatedly suggested to Lee that he eliminate the expense of the farming equipment and use livestock as a soil-building and fertility tool.

That recommendation finally resonated with Lee and he and the boys started building fences, planting perennial grasses and getting serious about livestock. Motivated by Beth’s health scare years before, Lee was focused on producing food that was as nutrient dense and healthy as possible, including grass-fed beef.

Unfortunately, the Hitzfields had never finished cattle on grass before. Prior attempts at finishing cattle were done using non-GM corn, so it was a grain finished product. Their overall inexperience in grazing at that stage meant they were producing a rather lean beef product. Couple that with the fact that they were buying the cheapest cattle possible (i.e., roping cattle) and they ended up with lean, tough beef.

Because they also wanted to try their hand at direct marketing to the consumer, they initially passed out samples of their beef to extended family and friends. They quickly realized that the beef was not of high quality and the whole muscle cuts, steaks and roasts, were not a pleasant eating experience. Blaine even admitted that they would not eat their own tenderloins as filet mignon.

Enter Seven Sons and Direct Marketing

In January of 2000 they created the “Seven Sons” brand and launched their first major effort at direct marketing. That was when the Y2K craze was going global and the public was in a frenzy brought on by predictions that there would be widespread crashes of the internet and computer systems that would snowball into a crashed economy. Since their grass-fed beef was not a high-quality product, they took advantage of the fact that many consumers believed they needed shelf stable foods with a long storage life, which required developing a canned-beef product. During the Great Depression, canned beef was a staple for many Americans and it made an unexpected resurgence in 2000.

There were several advantages that a canned beef product provided:

- It was completely shelf stable and did not require cold storage.

- Once canned, Seven Sons did not have to worry about spoilage, so it gave them time to develop a strong customer base.

- Their lack of experience in properly finishing cattle on grass and the poor cattle genetics did not matter with a canned product, due to tenderizing, pre-canning cooking processes.

In addition to canned beef, Seven Sons also developed a beef jerky and a summer sausage. These items provided two more shelf-stable items that did not have to be produced from well-finished animals. During this time period, Lee visited health foods stores with canned beef and the other products under his arms, placing the products in local stores wherever possible.

The original Seven Sons canned beef

Stacked Enterprises

In the early 2000’s the Hitzfields were influenced by what people like Joel Salatin were doing with stacked enterprise systems wherein multiple species of livestock were raised on the same acres. They became convinced this was the path to further progress and success. So, they jumped in headfirst and soon had broiler chickens, laying hens, cow/calf and grass fed beef, pastured pigs from sows-to-harvest-ready pigs, plus sheep and goats. In addition, they were custom growing non-GM corn and soybeans and selling livestock feed to neighboring farms, along with growing several hundred acres of small, square hay bales annually. Lee says between the years 2000-2005 they “got into more enterprises than they could properly keep track of.”

In 2004, Blake got married and officially joined the farm. In 2005, Blaine followed the same path. In spite of all the enterprises, net revenue to share among the families was sparse. Blake and Blaine had to take off-farm jobs to make ends meet for their new families. They readily admit those were some pretty lean years financially and their primary stake in the farm was through their blood, sweat, and tears.

Mobile Hen Housing, complete with guardian dog

Turning the Tide

In 2007, a fortuitous event happened that started a definitive shift in the trajectory of the farm. A customer asked the Hitzfields if they could supply a pallet of eggs per week for their store. They quickly sourced 750 pullets (young chickens) from a farmer in Hershey, PA, and drove straight there and back, without sleeping, to bring the pullets home. That was the beginning of their current model.

This opportunity allowed Blake and Blaine to join the farm full-time. Money was still tight and Lee was giving them cattle as a part of their earnings. Blake and Blaine both had to find a way to survive on very little income, which was about $20,000 annually in those years. According to both, they ate a lot of canned beef, eggs, and heated their homes with firewood.

Their key to success during these lean years was a dogged persistence, a belief in what they were doing, and a willingness to always learn and educate themselves. The struggles they had witnessed Lee and Beth experience in earlier years formed a “bulldog attitude” within the boys. Blake and Blaine say they were so grateful to be back on the farm full-time that the sacrifices they had to make were well worth it.

Between 2006-2010, they kept their heads down and worked many long, hard days and Lee and Beth provided assets in return for the sweat equity. These years were the most pivotal as Lee and Beth gave decision-making authority to Blake and Blaine. The direction of the farm was now in their hands. Their ability to develop profitable stacked enterprise systems and a viable direct marketing business was their responsibility. This authority came with consequences though. If things failed, it would directly impact them and their families and there was no safety net.

The New Era

The two brothers say being allowed to develop and express their entrepreneurial spirit was both frightening and exhilarating. With Lee and Beth decentralizing the decision making and allowing the boys to grow their business skills, it provided an opportunity for all the boys to become independent. They were able to more fully develop their own distinct personalities, skillsets, and enterprises.

What many who are not in the farming business may not realize is that this is unique among many farming families. It is quite common to see a 40–50-year-old son or daughter actively working on the farm, but with little to no decision making authority. Often, it is not until the parents pass away or retire that the sons or daughters working on the family farm finally get an opportunity to make the management decisions. Lee is often asked how he has been able to “keep” the boys on the farm and working for him. He quickly corrects them and states that his sons work with him, not for him.

Another in a string of pivotal moments came in 2010 as their business was growing and there were mounting responsibilities. They found that the accounting among the various enterprises was getting “fuzzy” and more difficult to manage. They realized they needed to stay focused and to know where their profits were coming from and where they were possibly losing money. They also needed to understand how best to reinvest in their businesses and to allocate duties and responsibilities.

At that time, none of the boys had gone to college or taken any business classes. All they knew was that at the end of the day they were either going to make money or lose money. Then they decided to do something very bold. They assigned leadership roles for various enterprises to a specific person and then held each other accountable for their decisions and performance. Each brother owns his own specific enterprise(s) and sells into the marketing side of the business. They hold weekly board meetings to determine the best steps for the next week. The family believes that the discipline and intention instilled in all they do fosters incentive and synergy and that their “Not-to-Do” list is every bit as important as their “To-Do” list.

The family had to learn how to divide and conquer and work through all the legal processes of a fast-growing enterprise. Their management decisions allowed their marketing efforts to be far more focused with the resulting sales generating cash for reinvestment in the business. Blaine and Blake say the decisions they made in 2010 on how to restructure the business paved the way for an explosion in business that continues to this day.

Keys to an Expanding Business

Since those pivotal decisions in 2010, the family has adopted the philosophy that you need to be keenly aware of what you know, what you are good at, and then be humble enough to learn from others those things you do not know.

Each say they have key mentors in their ongoing learning process, including the previously mentioned Ray Smith and Joel Salatin. They also point to others who have been instrumental in helping them along the way, including regenerative farming pioneer and consultant, Gabe Brown, Allan Nation of Stockman GrassFarmer magazine, and David Pratt of Ranching for Profit. They became very active in the Grass Fed Exchange and met other influencers through that organization, such as Ray Archuleta and Allen Williams, Ph.D. Allen has worked with them to help adopt adaptive grazing practices, improve their grass finishing capabilities, and hone their cattle genetics.

In 2013 they decided to hire both a fractional CFO and peer coach, Michael Hyatt, for peer-to-peer relationship coaching sessions. Through these sessions, they gained an appreciation for balancing growing the business with quality of family life.

The Grass Fed Exchange has been a huge influence on the family and their business and have been loyal participants and sponsors. The extensive networking and relationship development offered by the Grass Fed Exchange has been crucial to their ongoing business development.

Marketing and Sales

By 2014, the business was routinely running low on product due to rapidly growing sales. Seven Sons soon realized it needed to foster development of a farmer-supply network that could fill the gaps in supply. The development of this network led to some remarkable relationships with other farmers who are now part of the Seven Sons family of suppliers of regeneratively produced and pastured proteins. Seven Sons now supports their own eight families and a number of other employees. This business association is also supporting other farm families and, in the process, revitalizing rural economies.

Since 2010, Seven Sons has focused heavily on building out effective internet platforms for growing customer sales and access. They have strategically used social media to build customer relationships, trust and transparency. Video segments have been instrumental in connecting with customers in a personal way and conveying the story of the farm and Seven Sons’ value proposition.

Cold Storage at Seven Sons Farm Warehouse

The brothers say one of the best business decisions Seven Sons made was to hiring Chad Graue as their Director of Digital Marketing. They first hired Chad as a consultant to help refocus their attention on internet/digital marketing but his work with Seven Sons made them realize they had fallen behind on their marketing strategy and deployment. Chad was hired full time and has taken their marketing to levels they never dreamed possible. They say in trying to keep up with all the many facets of their growing business, they had lost track of innovation. So, they went back to their premise of “know what you know and hire those who know what you do not.”

Blaine readily admits that hiring Chad on a full-time basis was not inexpensive, noting that they paid Chad more than they pay paid themselves. But, within one year of his hire, Chad grew their business by $1 million. Chad has been a part of the team for four years now and their fast-paced growth continues.

This example dispels another common excuse many farmers use to not grow their business, particularly the marketing side of things. We often hear, “I can’t afford someone like that,” but hiring the right expertise, even if through consulting, can make a farm far more money than trying to do it all “in house.” Seven Sons recognized and identified their weak link and hired the expertise needed to fill that void.

Leveraging Technologies and Creating New Businesses

Seven Sons has a relatively new business that was an organic outgrowth of their efforts to leverage software technologies to streamline their business. In 2014, they started working with a water delivery provider who happened to have a knack for software coding. He started building code to solve their internal business bottlenecks. The new platform, called GrazeCart, became the internal engine through which all the business flows. They now pay a two full-time software engineers $250,000 annually to create value through software to streamline every facet of their business and customer experience.

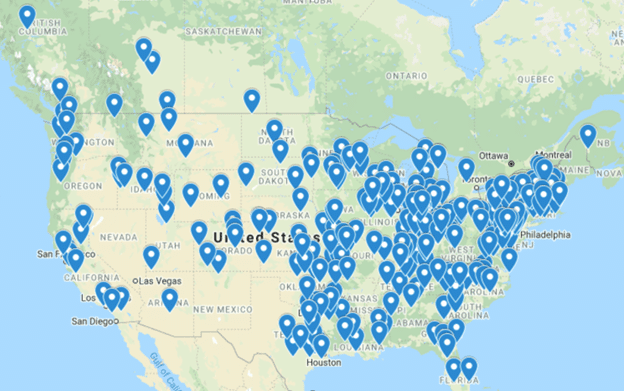

When they decided to launch GrazeCart as a stand-alone business beyond meeting their own internal needs, Gabe Brown (referenced earlier as a mentor) became one of their very first customers. They now service more than 450 farm business customers who utilize GrazeCart as their online marketing platform. Each year over $70,000,000 of regenerative foods are to consumers through the GrazeCart Platform. Working with other farms has proved advantageous for Seven Sons by providing an umbrella of knowledge and innovation through constant interaction, which has greatly expedited their learning.

The Hitzfields say GrazeCart is built with the consumer in mind first and then to serve the actual business. It is also built as a software business and has been a gamechanger for many farms that direct market, allowing them to move to the next level of success.

Distribution of farms using GrazeCart

Interestingly, the water delivery provider who moonlighted as a software coder is now a full-stack senior software engineer and has gone on to develop software for JackBe, a venture funded online grocer.

Evolution

Through the years, Seven Sons has gone from giving product samples out to family and friends—and selling canned meat at health food stores, their little farm store and farmers markets—to product fulfillment through buying clubs and home delivery business. They’ve even become masters of internet marketing. Each step along the way was important because it taught them how to grow naturally and in succession. They learned that getting product to people is not the same as knowing who those people are. They had to create awareness of Seven Sons and their story and spent countless hours at farmers markets and at their on-farm store learning how to relate to customers.

Seven Sons Farm Store, located on site at the farm

When they first started with online shipping, they spent their first $100,000 investment to generate $100,000 in revenue, which also highlighted the importance of grassroots efforts and quality products. They learned that word of mouth advertising is immensely powerful and that every customer must be “treated like royalty.” Conversely, they also learned that sometimes the best strategy is “to fire a customer” because not all customers are good for your business. According to Blake, if a customer continually makes life hard on their team, then they may no longer be worth servicing as a customer. However, for those customers who are respectful and loyal, “you must make them feel like the relationship they have with you is exclusive.”

Farm Warehouse Expansion

To grow their business, Seven Sons had to navigate management and leadership issues including how to transition from a small family farm to a major marketing business and how to onboard new people who could fill the gaps in knowledge, skillset, and expertise. By using a combination of consultants, vendors and employees, they have forged a remarkable team of highly skilled and motivated individuals who are excited to come to work every day.

Additionally, they have forged strong relationships with their partnering farmers and with their meat processor. They look for aligned values and common goals among all their partners and believe in finding the right people and then getting out of their way.

Blaine and his wife Charis have six children, 4 boys (ages 13, 10, 7 & 1) and 2 girls (ages 5 & 2). They recently completed building a home on the family farm where they live and homeschool their children. Their two oldest boys already enjoy working after school and in the summers gathering eggs and packing orders.

Brice works full-time on the farm as the director of Hen Gear and helps with innovations within the hen enterprise.

Brock and his wife Katrina live near the farm with their year old son. Brock works full-time as their Creative Lead creating and managing all things branding and digital assets.

Brooks & his wife Catherine both work full-time on the farm. Brooks is the CEO of GrazeCart & Catherine works as the executive assistant to our leadership team.

Bruce & his wife Alyssa live on the farm and have a 3 year old son and 1 year old daughter. Bruce is the director of laying hen operations and Alyssa manages social media for their growing Fresh Egg Co brand.

Brandt & his wife Marissa live near the farm and both maintain a roles on the farm. Brandt is the director of supply chain and works closely with Blake to manage supplier & processor relationships. Marissa works in the on-farm retail operation and manages social media for the Seven Sons brand.

Recent Developments

Seven Sons has implemented several changes in recent years. Previously, they were selling products through buying clubs where they delivered to established pick-up locations every Saturday using their three sprinter vans. Customers would pre-order and then pick up their order at the designated location. They have now transitioned to home delivery. It was a data-driven decision because their buying club sales were trending down while home delivery was trending up. The change came together during COVID when people avoided gathering with big groups of people while picking up their meat orders. COVID opened the opportunity to focus on delivery to individual customers as an added convenience. Blake says the decision was a “leap of faith” because the buying clubs had been generating gross revenue of well over a million dollars annually.

Home Delivery Refrigerated Sprinter Vans

Blake admits they were uncertain what percentage of their customer base would adopt home delivery. Home delivery costs more than delivering to a pickup location, and it was unclear if customers would pay that difference for the convenience. Initially, they offered an attractive discount on customers’ first-time orders to help them get used to the product being delivered straight to their home.

Throughout the home-delivery transition, Seven Sons had to address various customer concerns including whether the product would arrive frozen or thawed out and compromised, and whether the product would arrive on time and every time. Offering a good discount to get people to initially try the home delivery service proved successful as the adoption rate was quite high. While they did lose some customers, it proved a worthwhile decision and the change simplified and streamlined their fulfillment system as well.

Next Steps and New Directions:

Their next step in marketing and distribution is what they call “Subscribe and Save,” which is similar in design and function to Amazon Prime. They launched this service in 2022, after researching and developing the concept for six months. Their goal centered on making things as seamless and easy as possible for their customers to make transactions without going through the work of placing the same order every single time. Blake admits they used to pride themselves on how their loyal customers would place orders every time they wanted something, but now recognizes the element of inconvenience that comes with that approach. They remain focused on eliminating as much of that inconvenience as possible.

Packing Orders for Shipment to Customers

The adoption rate of the subscription service now accounts for 70% of all online sales. The default option for subscribed customers is to receive their selected items every eight weeks. They can choose to opt out of the subscription, or they can adjust the frequency of shipment and the content in the order. As a bonus, Seven Sons includes a free item with every delivery. This may be a pack of bacon or a pack of ground beef and they also offer a 5% savings to those who remain subscribed. The outcome of these initiatives has been increased customer loyalty and customer spending on an annual basis. Even early in the transition process, Blake reported per-customer sales went up by roughly $200/year. With more than 10,000 customers, this translates to a substantial increase in gross revenue.

Blake noted that prior to their “Subcribe and Save” offering, their average customer 12-month value had been about $500. However, since incorporating the new service, they are up to a $700 12-month customer value. They also noticed that every summer after school lets out, in what Blake dubbed “farmers market and vacation season,” customer routines and habits get disrupted and as a result, they don’t place orders. Plus, they are at home less, so customers are not sure if they'll have time to get orders in the freezer. Usually, with farmers markets going, Seven Sons noted a slump in the summer months, with sales picking back up in the fall. In contrast, in 2022, with the subscription service, there was no summer slump. They maintained strong sales coming out of spring and continued growth through the summer, which hasn't happened in many years. Blake attributes that to the Subscribe and Save service and to the additional Google and Facebook advertising they are doing.

Blake says the decision to increase their advertising budget was scary because of the challenge of quantifying the return on advertising investment. Every farm differs in what they can afford to spend to attract customers. Blake said they have spent significant time and effort collecting data in the last few years to better inform their ad-purchasing decisions. Initially, they were advertising on Facebook, spending $5,000 to $10,000 per month but in 2022, they decided to “really put some meat behind it,” by doubling to tripling their advertising budget. Blake says they currently spend about $100 to gain a new customer and estimate they can afford to spend about $150 to do so, which represents an opportunity to continue to grow their customer base.

In short, Seven Sons’ focused advertising strategies, combined with the subscription plan, are proving to be a recipe for growth and sustained customer retention.

Shipment Concerns

The Subscribe and Save orders are shipped primarily using UPS. Recurring orders are queued on Monday of each week and fulfilled on Monday and Tuesday of that week. All shipping is fulfilled through UPS or other regional carriers, which Blake says works well, but the arrangement also creates dependency on outside partnerships. Their carrier relationships are vulnerable in today’s economic environment, because of the high demand for logistics. Blake recognizes that with UPS or FedEx, Seven Sons’ shipment volume is “not even a drop in the bucket.” With the amount of care and intentionality that goes into the handling of the packages of perishable products, on-time delivery rate is central to their success. Seven Sons used FedEx in the past, but they dropped to 85% deliverability, which he described as “awful.” In packaging, they build in an extra day guaranteed into every box so if the shipment gets delayed, they have adequate refrigeration cushion to still be okay. Second-day or over-the-weekend delays are disastrous for the business. UPS’ delivery rates were 95%+, which is still not where Seven Sons would like, but is much better than what they experienced with FedEx.

Moving forward, Seven Sons is exploring opportunities to partner with larger, more regionally based carriers including multi-state carriers with scale like LaserShip. Blake says the potential to develop relationships with them is better than with UPS because of the service and the care that goes into packaging and handling. He knows of other farms using these alternative carriers, but a key challenge for Seven Sons will be meeting the minimum number of orders that must hit the system before shipping, which highlights the importance of continued growth. Blake sees an opportunity to partner with other farms and capitalize on group buying. And because these smaller carriers are more regional, he thinks they can do a better job of cutting costs on boxing materials since the packages are not traveling as far and many of these carriers’ facilities have coolers. Both offer an opportunity to cut packaging and delivery costs, which can lower customer shipping costs.

About 50% of Seven Sons customers are within a one-day, 200-300-radius shipping zone from their farm. But they also sell nationwide. The fastest growing distribution channel is their three-day shipping, which includes Florida, into the Northeast, and even as far west as California. The remaining sales are either wholesale or through their farm store, which continues to grow.

Fresh Egg Company

Seven Sons recently launched a new brand they call Fresh Egg Co. They had always sold eggs through their website, SevenSons.net, and they’ve offered a multi-temp box with a frozen meat compartment and a separate compartment for the fresh eggs. They’ve also sold to Whole Foods, with distribution to 80 retail stores but they are looking to create more consistency in their egg purchasers because retailers like Whole Foods can be variable with their orders. For example, one week they may order five pallets, the next week eight pallets. Whole Foods also has periodic sales; they want their vendors’ items to go on sale 2-3 times per year to drive customers into their stores and they require their vendors to commit to their merchandising plan. When Whole Foods has a sale, they’ll double their orders, which presents inventory management challenges. After considering their options for a couple of years, Seven Sons decided to also launch Fresh Egg Co., an egg subscription service.

Seven Sons Pasture Raised Eggs in Whole Food Market

These are the types of decisions that many who choose to direct market must make. Selling through a major retailer like Whole Foods may seem attractive and lucrative at first, but there are also concessions that have to be made. Suppliers can be cut off overnight by many retailers, potentially leaving large inventories of perishable product and no sales outlets. Seven Sons made a strategic business decision to have more control over their product inventory and product sales.

Through Fresh Egg Co., customers sign up for a subscription of either four or eight dozen eggs delivered every four weeks. Customers can also opt for a quicker delivery if needed. The product-creation to product-delivery timeline is as follows: Farm staff gathers eggs in the morning and the eggs arrive at the packing facility by noon; the eggs are packed in the afternoon and then loaded on the UPS truck that evening. Customers within a one-day shipping zone from the farm have their eggs as early as 8:00 a.m. the next morning, making Fresh Egg Co. eggs “pretty much the freshest eggs in the world delivered right to your door.” The eggs are not washed, so they still have their fresh bloom on them, the protective coating that allows them to be stored without refrigeration.

Seven Sons launched Fresh Egg Co. in August 2022, with the goal of 800 subscribers by the end of September; they exceeded their goal in just a few weeks. Blake feels the onboarding went well, even though they are still working out some kinks. While it’s a relatively new brand, Blake sees their strategy as having the potential to facilitate more consistent ordering so that they can better plan production around their customers’ expected demand. “One can't just tell a chicken to stop laying an egg or to produce a couple of extra eggs on a given day,” he says. Fresh Egg Co. is providing more predictable production conditions while also benefiting their customers by getting fresher eggs delivered to their door at a cheaper price than when Seven Sons was marketing them using the multi-temp boxes. They no longer offer eggs through the Seven Sons website. Customers who want their eggs must order them through the Fresh Egg Co website.

Because COVID catapulted their business into needing additional storage, Seven Sons has recently moved into a new 10,000 square foot warehouse.

Growth of Livestock Enterprises

Thousands of paying hens on pasture at Seven Sons

Seven Sons sold their cow herd in 2017. Instead of maintaining their own cows and producing calves, they partner with other farms to supply calves for grass finished beef production. They select primarily Red Angus, Black Angus and Murray Grey crosses. The calves weigh about 800 pounds when Seven Sons purchase them in May of each year, with a goal to have the calves ready for harvest by late October and into November of the same year. They focus on achieving the cheapest gains possible on their farm during the active grass-growing season, which also assures the highest levels of favorable fatty acids and phytonutrients in their end product.

Their chicken enterprises have continued to expand with the laying hens being the fastest growing production enterprise on the farm, increasing their laying hen flock by 5,000-6,000 hens in recent years. Blake estimates they have around 15,000 laying hens on pasture. During the summer the hens are moved daily to fresh grass, a process Blake describes as “intense, but fun, and yielding a great product.”

Seven Sons added sheep in 2022, which is something Blake has long wanted to do, but felt they previously lacked the bandwidth to integrate the effort into the enterprise. One team member has assumed responsibility for the 500-ewe sheep herd. Lamb sales on the website have been slow starting out, but demand is picking up. Blake says that while they haven’t devoted marketing resources to lamb sales, that is likely to change because they are more motivated to see the enterprise thrive and are also developing strategies to make it easier from a cost standpoint for customers to buy lamb. Marketing is proving a bit tricky because they can generate similar returns selling on the conventional market as they are selling processed lamb, but they are exploring ways to reduce processing costs. In 2022, they experimented with an eight-piece lamb which had larger portions that the customers could either cut up themselves or put it in a crockpot as a large roast. The limited quantity processed that way sold out relatively quickly. Blake expects to expand that offering since it was a huge cost savings for their customers.

The sheep breeds Seven Sons raises are hair sheep meat breeds, primarily commercial Dorper. One longer-term goal for the sheep is to integrate them into areas with solar panels. A location less than 2 miles from the farm has committed about 1000 acres to solar development starting in the next couple of years. Seven Sons is in discussions with the owner about grazing sheep under the panels. This dual use situation is called agri-voltaics and is a fast-growing opportunity. Currently, too many solar farms are not set up to facilitate agricultural food production, creating an “either solar energy or food production” conflict. Agri-voltaics allows landowners to combine both on the same acres.

The possibility of gaining access to additional grazing acreage was the impetus behind the decision to start raising sheep. However, Blake didn’t want to wait until they got the green light to graze the solar fields before they began raising sheep. He knew there would be a steep learning curve since they had not raised sheep before so he wanted to get a couple of years of experience before they try to raise sheep under solar panels on someone else’s land. Blake says that even if the grazing-under-solar opportunity never develops, they will likely keep the flock because he feels they have a place on the farm. Another motivating factor supporting the sheep enterprise is that they are safer to handle than the cattle. With Blake’s five children and the nieces and nephews getting involved in farm activities, the sheep enterprise provides an opportunity for the younger generation to gain experience with livestock without the accident risks associated with larger livestock species like cattle.

Seven Sons has honeybees on their farm; however, they don’t personally own them. They partner with someone locally who manages the hives, and who produces honey on shares with the Hitzfields. Blake loves honeybees and honeybee production, and sees it as an enterprise he wants to add in house, but he admits, he can't do it all. Blake actually had the bee owner put hives close to his house so he could see them frequently.

Processing Concerns

Seven Sons contracts its slaughter and meat processing with two facilities; one does the harvest and the other does the further processing, in what Blake calls a “great hand in glove fit with Seven Sons.” The processors have been able to do things for Seven Sons that Blake didn't think was possible, which has allowed Seven Sons to grow. Byron Center Meats is a forward-thinking processing facility that wants to continue to grow as demand for processing skyrockets. The company recently purchased another facility, doubling their processing square footage and their cooler space. Seeing Byron Center investing into the future brings peace of mind to Seven Sons as they continue to grow. As Seven Sons expanded and began to near a processing ceiling, their processor would “blow the ceiling up,” and do everything possible to meet their processing needs. While their processors are about 3.5 hours from the farm, Blake says he wouldn't think of not using them because they are excellent partners.

While their slaughter and processing partners are unseen from a customer standpoint, Blake says it’s that unseen piece that brings it all together. Seven Sons can spend two years raising the animal, investing all that care and intentionality into it, then take it to the processor and be instantly at risk. How the animal is treated prior to slaughter and how they are processed plays a very large role in end-product quality and consistency—and whether everything will meet customer standards. Blake says their customers ask questions about the slaughter process, and they want assurance that the animals are handled humanely. These are real questions that the Hitzfields never take for granted.

Seven Sons only works with USDA-inspected facilities for slaughter and processing because they sell across state lines. Blake says there are many state-inspected facilities closer, and they do a good job, but will not work when you sell product interstate. The farm is also inspected by the USDA. While they don't need on-site processing, the inspectors come through every few months to make sure everything looks up to par. Blake says they try to make their job easy. For example, inspectors don't want to see state inspected meat in the same freezer as USDA inspected meat. Should that occur, the farm would have to prove source and destination for that meat, a real logistical nightmare. Seven Sons doesn’t use any state-inspected facilities to keep this part of the process simple. “Farming is hard enough, we don’t need to do things like that to make it even harder,” Blake says.

For quality control with the cattle Seven Sons purchases, cooperating producers sign a production protocol the Hitzfields have been using for 15-20 years. They have about 50 other farms producing cattle for them covering the live beef production supply chain, from cow-calf, through backgrounding and finishing. Early on, there was careful vetting and working with those producers, many of whom have been with them for a long time now. Blake says the job is getting easier in many respects because their cooperators know exactly what works on their farm, they know what Seven Sons expects and their production protocols and practices. Expectations are clear; the upfront work is paying off. The consistency that Seven Sons sees is improving every year.

Seven Sons’ processor is not set up to grade livestock so they do their own internal grading. They get a picture of every single rib section and hire an outside independent consultant to look at the carcasses and provide an evaluation. That provides useful feedback Seven Sons, in turn, provides to their cooperating producers. Blake credits Allen Williams, Ph.D. of Understanding Ag, for his assistance in setting this grading system up. It has been very beneficial for Seven Sons and for their producers as they make progress paying premiums based on animal performance and the resulting grade. It’s incentivizing producers and customers also benefit from a more consistent product. Blake is focused on aggressive improvement and identifying strategies to do it better.

While many already have, Blake says he hopes to get all of their cooperating producers to attend a Soil Health Academy or other regenerative agriculture workshop. In addition, they also invite the producers to visit their farm to observe the regenerative farming principles and concepts in practice.

Resources for Learning

Early in their transition process, there were few resources available to help Blake and his family learn about regenerative agriculture. Watching the regenerative movement grow and seeing the abundance of educational resources become available is very encouraging. The peer-to-peer learning with other farmers is powerful and Blake says the regenerative community differs greatly from the conventional agriculture community, where many producers don't share much of their information, “as if it were top secret.” In contrast, in regenerative agriculture, because it's a grassroots movement, producers opt to work together, share insights, encourage each other to help the movement grow. While it's growing by leaps and bounds, there is still a long way to go. Blake says that what organizations like the Soil Health Academy and Understanding Ag have done for Seven Sons farm and for other farms is really inspiring. “They have basically created a whole system, a whole business around that, helping farmers and ranchers,” he says.

Neighbor Responses

When asked what their neighbors’ responses have been to their transition to regenerative agriculture over the years, Blake said it has been mixed. Some have watched the process and have been inspired, but sadly, not many. Others are convinced the Hitzfields are crazy and want nothing to do with them. Blake is not bothered by that response; he respects that decision. And then others recognize their good relationship with Seven Sons, but they don't grasp what Blake and his family are doing. Perhaps they think the Hitzfields just got lucky. Many are curious, but not committed enough to dig in to find out what's going on. Seven Sons has great neighbors, and they work hard to maintain those relationships, whether they are farmers or people who work in town; their neighbors are their friends. They get to listen to the chickens, all 15,000 of them. Blake said it's crazy, some mornings, when the wind is just right, he can hear the chickens from a mile and a half away as he heads out, so he knows that everybody else within that mile and a half is hearing them as well.

Blake says he believes his community is similar to others, where some farmers are progressive and interested in learning, while others are reluctant. And it comes down to the reality that, in general, people don't like change. It is hard and uncomfortable. Until someone is forced to decide, oftentimes they just don't. Many farmers are comfortable where they are and those with adequate equity in their land can ride out the ups and downs, so they're not forced to change. Some farmers are being forced to change production practices by landowners. When landowners want their farm to be farmed differently, they will require tenants to make the changes and implement regenerative practices. Blake says it comes down to how comfortable people are. Until they get more uncomfortable, for example, due to financial or health issues, they don’t change. That is exactly what happened to the Hitzfields. They got to the point where they didn't believe in the conventional food system anymore—a system they were once a part of. And because of what they saw with Beth’s health, they knew they couldn’t continue down that path. Blake admits that their farm was going broke too, which provided additional motivation for change. “That's when people decide to do something different, when they are forced to change,” he says.

Blake observed that a farm cannot be organic by neglect. They continually push toward improving soil health. While removing harmful aspects of conventional production is important, rebuilding the right way is key too. They started checking plant brix values when juicing for his mom and they still take plant brix readings, but now on produce from their own garden.

PRODUCTION AND FINANCIAL PROGRESS:

The Soil

Seven Sons has been tracking soil organic matter (SOM) for the past ten plus years. When they started into the transition to regenerative production, SOM measured from 0.5%-2.0% in most fields, with a few fields at 3.0%. Now they are averaging 5.0%-6.0% organic matter in most fields.

Wildlife, Birds, Insects

Blake says they have observed a significant increase in wildlife, birds, and beneficial insects in recent years. In fact, bird and insect populations have exploded. Blake has not had time to pursue birdwatching yet, but he says he wants to as he becomes more intrigued with the diversity they are observing. He is open to allowing customers to start bird watching on the farm at some point because activities like birdwatching provide an opportunity for new customers to learn about the farm and see the fields and pastures. He called it a “garden meeting.”

Highly Aggregated Soil at Seven Sons Farm

At their supper table recently, Blake asked his family what they thought the Garden of Eden looked like. “Everybody had kind of their own idea of what it looked like,” he says, “but there were many things in common: trees, water, lots of different plants, tall and short, lots of flowers.” In Blakes’ mind, it’s a massive garden, which is what he feels their farm is. He feels he needs to communicate that concept to their customers. Internally, he feels that he is stewarding his garden as a European-style garden in America. In America, most think of vegetable patches when they think “garden.” In contrast, a European style garden has much more context and diversity. Specifically, Blake wants their farm to resemble a wildlife preserve or natural garden where they allow the land to express itself. They are there to massage and tweak it here and there while letting it take the form and shape it would naturally want to take.

In the spirit of that philosophy, Blake says he wants to research planting trees on the farm. They want to explore incorporating trees into their open pastures in such a way that the trees don’t hinder moving their chickens through the pasture. He sees adding trees as a big plus.

Key Numbers and Impact:

Animals produced & direct marketed by species:

CATTLE:

Home raised: 150 head

Producer raised: 1,200 head (40 partnering farms)

Total 1,350/year

PORK:

Home raised: 400 head

Producer raised: 900 head (5 partnering farms)

EGGS:

Home raised: 350,000 Dozen (15,000 hens)

Currently no additional producers but that will change later this year

SHEEP:

Home raised: 1,200 Ewes

We currently only harvest and direct market 300 lambs/year

------------------------------

Margins by Species: (Combined Production + Marketing Margin)

Beef 53%

Pork 43%

Lamb 56%

Eggs 38%

------------------------------

People Impact:

- 40 family members and staff on payroll

- 11,000 active families who purchase food annually

------------------------------

Impact of Other On-Farm Enterprises

HEN GEAR

https://hengear.com

Hen Gear provides rollout nesters and pastured poultry equipment to farms and homesteads across US & CA

GRAZE CART

https://www.grazecart.com

GrazeCart provides 450 farms and direct marketers in the US & CA with website and e-commerce software.

Our farms sell $70,000,000 of regenerative foods to consumers annually through the GrazeCart Platform.

FOOD CHAIN WARS Podcast

https://www.foodchainwars.com

Blaine & Brooks help farms by sharing proven strategies for direct marketing success.

Podcast Impact: 50,000 unique podcast downloads from over 50 countries

Total sales of Seven Sons Food Products:

- 11,000 laying hens producing over $1,300,000/year in gross product

- 1,300 hogs producing over $1,700,000/year in gross product

- 1350 beef producing over $5,400,000/year in gross product

- Total annual direct market sales topping $10 million, including sales from our partnering producers.

Individual enterprise analysis shows that each major pastured protein enterprise is producing significant net revenue for the farm.

Net Revenue Per Acre from Major Enterprises.

| Enterprise | Net Margin/Acre |

| Grass Fed Beef | $970 |

| Pastured Pork | $1510 |

| Pastured Eggs | $5500 |

Note: Not all enterprises are operated on every acre.

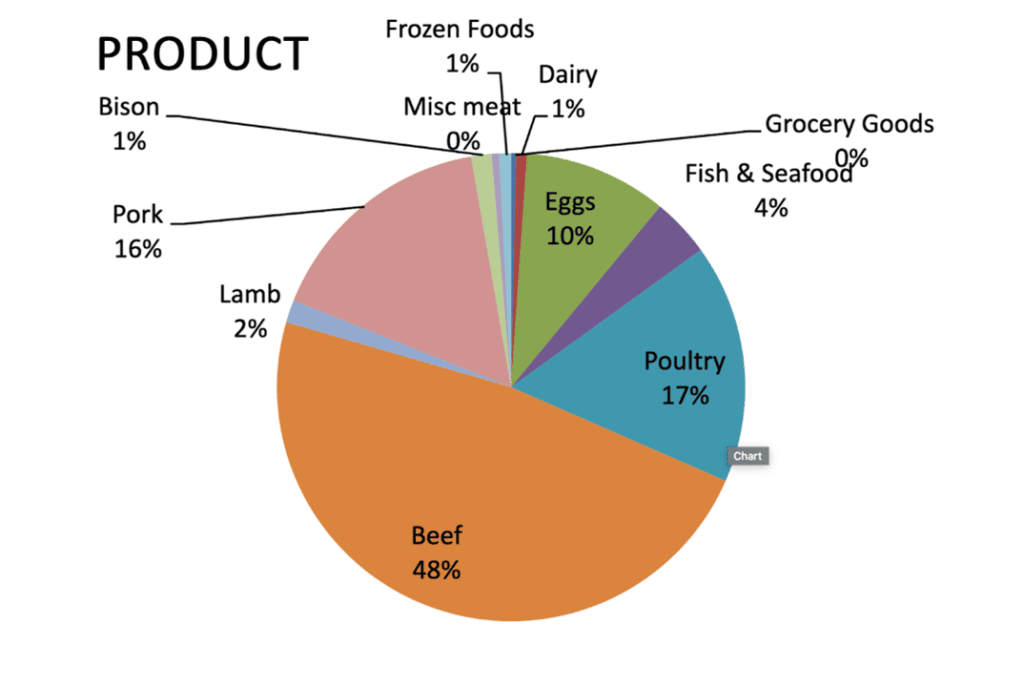

Sales for all items are broken down in the chart below. Beef is just under 50% of all sales, with poultry, pork, and eggs coming in second, third, and fourth, respectively.

Product Sales Breakdown for All Items Offered.

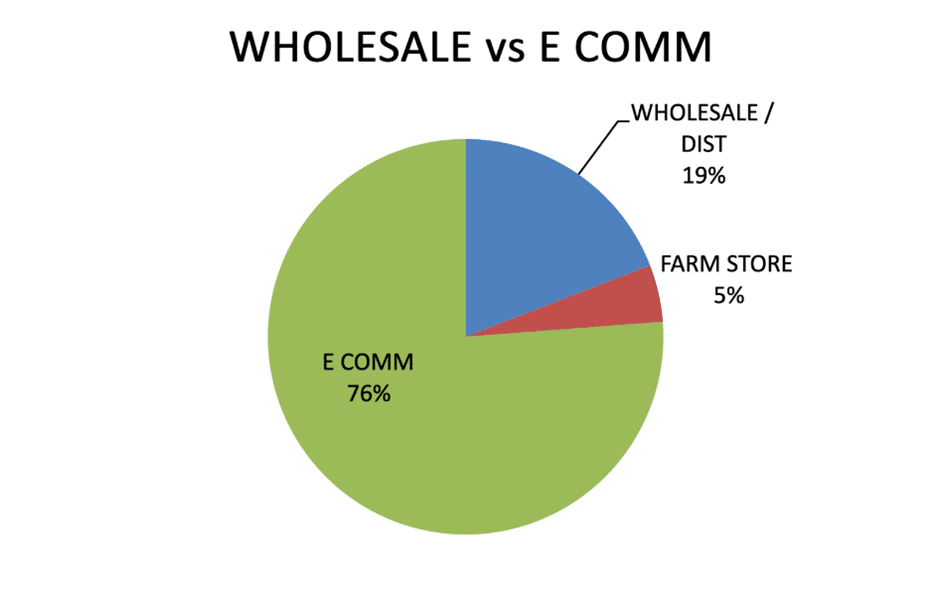

E-Commerce sales (including home delivery) make up 76% of all sales, with wholesale distribution comprising 19% of sales and the farm store making up the balance (5%).

Seven Sons has maintained its 550 acres without the need to grow their own land base. Most conventional farmers have the desire to continually grow their land base through purchased and/or leased land, believing it to be the only way to grow revenue. However, the Hitzfields, like many other regenerative farmers, have found that more land is not the answer to profitability. Just like the Hitzfields let all their leased land go, so have other regenerative farmers. Instead, their focus is establishing multiple enterprises that are symbiotic with each other and working with other farmers to cooperatively produce nutrient-dense foods for their customer base. It is all about optimal utilization of the acres they own and creating opportunity for other farming families.

Specifically, the Hitzfields want to implement production and marketing strategies that generate the highest possible returns on those 550 acres with their three primary enterprises, beef cattle, pastured hogs, and laying hens. Although they are not adamantly opposed to expanding production or growing their farm size, they feel that impacting more acres through growing a farmer network is far more advantageous. Blake sees their growth as simultaneous business growth and personal growth.

Early on in their growth curve, they ran out of acres for expanding their cattle herd, but that limit provided incentive to seek out and develop relationships with other producers to help them generate adequate supplies to meet their ever-expanding demand. Cattle production is so land extensive and cost prohibitive that purchasing more land just for the cattle is not feasible. They are already facing land constraints for their laying hen enterprise, and to remedy this, they are considering purchasing additional land, securing long term leases, or partnering with other farmers to grow their egg production.

Inside the Fulfillment Warehouse at Seven Sons

Recommendations for Someone Considering Regenerative Agriculture

Blake’s recommendation for those considering a change from conventional production to regenerative agriculture is to “walk before you run.” While it’s tempting to just dive in headfirst, he says it's important to remember that there is a learning curve. So, be willing to accept that there is a learning curve and go slow. Make incremental progress as you learn more. Learn from mistakes made; they’re inevitable so why not view them as learning opportunities? And usually, you have more mistakes to make, which was their experience anyway. So, starting slow and really focusing on the process is key.

Some aspects of a transition will depend on the type of farming but for those considering something like Seven Sons’ type of farming, Blake recommends they raise animals that create a rapid turnaround for the invested capital—animals like chickens, pigs, sheep, goats, honey, and other poultry enterprises. Cattle require the largest upfront investment and fewer head can be run on the same acres relative to the smaller species. It is not that they don’t have a place and their soil-building impact is appealing. So, when integrating cattle, it can be beneficial to do what the Hitzfields are doing and buy qualified feeders that can be finished within a single grazing season. Blake especially likes sheep, because the conventional market is strong enough that the potential for a profitable business exists whether you direct market lamb or not.

In Blake’s opinion, cash for initial investment purposes always king at the end of the day. He recently corresponded with a college student who wanted ideas for starting his own business when he graduates. Blake recognized the student’s passion to farm regeneratively, but he cautioned him about his focus on cattle. Blake tried to explain that burning passion only goes so far, and the honeymoon phase will go away quickly if the business is not profitable. Blake stressed that there is a balance between doing the right thing because you believe in it and approaching it from a business standpoint. He encouraged that student to consider what he can afford to do when he starts his business and urged him to make longer-term plans, asking him where he wants to be in 10 years. “It’s okay to not be there immediately when he starts out,” Blake says.

Blake acknowledges that farming regeneratively requires a lot of work, especially early in the learning process. He has seen so many young people jump in, then flounder, not realizing they need a community, a support system to help them through the process. It's too easy for most people to get tunnel vision and just focus only on their own farm, he says, and to feel they are the only one with urgent problems that need solving right now. Everyone faces that, especially starting out so Blake encourages others to reach out and ask questions adding, “There are no dumb questions.”

A key principle in regenerative agriculture is diversity. Blake cautions, though, because the more diversity a farm has when it comes to livestock, the more difficult it can be managing those enterprises. He points out that healthy soil with everything going for it is a self-managing system. It's complicated and complex. Managing regeneratively provides soil with the opportunity to function as it was designed. Adding the complexity of a poly culture with multiple enterprises, multiple lifestyle species, multiple marketing channels, and multiple employees, is a system that does not self-regulate. The farm management must do it, which takes bandwidth. There is a difference between diversity from a soil health standpoint and diversity from a business standpoint. Too much diversity in a business can be disastrous, but it is needed to operate regeneratively, so there are trade-offs; things must be in balance and what balance looks like differs for every farm. Blake emphasizes the need for awareness of how complex a regenerative system is from a business standpoint and how burdensome it can be managing all of the moving parts simultaneously to generate return on investment.

The concept of regenerative farming is broad, it brings in a multitude of different aspects of the farming community: farms that are row crop and cover crop focused; farms, like Seven Sons, that are strictly livestock focused with no row crops; and farms that are a blend of both. Blake suggests that understanding basic economics and farm financial management is important, not just for those considering a change to regenerative, but for all farmers. To be successful, he says one needs to understand how to determine enterprise profitability, properly allocate overheads, enterprise planning and resource allocation. This can be challenging to monitor and track, but there are tools available to help.

There are different aspects to marketing too, ranging from using conventional markets to marketing directly to consumers, and combinations thereof. Understanding the various marketing options a farm has been important, too. The Hitzfields spend a lot of time on marketing at Seven Sons because they realize that there are many farms producing great and healthy products, but the cruel reality is that the best products don’t always win in the marketplace. How do farmers promote their products in a way that attracts customers to their farms? Blake encourages farmers to grow into their marketing strategies. Through their experience and the GrazeCart business, the Hitzfields educate the farmers they work with, helping them recognize trends and develop strategies to respond. Blake stresses that farmers need to commit to effective marketing.

He also encourages farmers to monitor outcomes of their marketing strategies and to be ready to head in new directions as needed. Seven Sons realized this when they hit their own plateau after relying on periodic emails throughout the week, an email on Sunday mornings, some Facebook posts, and word-of-mouth advertising. The Hitzfields rightly concluded that if they did not change or interject new ideas into their marketing, they would not be able to achieve their goals. To remedy this, they hired a remote digital marketer who was paid more than they were making. Blake says as challenging as that step was to take, sometimes farm businesses must be willing to take “informed bold steps.”

Summary

Since the COVID-19 pandemic hit the U.S., Seven Sons has seen their already robust sales grow by another 400%. Although they quickly sold out of their own products, they have been able to leverage the relationships they developed along the way to continue to source regeneratively produced products for delivery it their customers. Their team has been stepping up to the challenge, working 16-hour days to get nutrient-dense food in the hands of those who most need it. Blake says their customers have never felt more grateful and thankful to have Seven Sons be there for them. When local grocery store shelves were running out of food, Seven Sons was still delivering.

The family is frequently asked today, “How have you been able to accomplish what you have with the farm and your sales?” They succinctly answer that the enormous sacrifice made by Lee and Beth was the catalyst, accompanied by the creation of a culture that facilitates growth, individual thought, innovation, and creativity. As a family, they have chosen to work together and stay together on the farm.

What is most important is the opportunity for the next generation. The model established by the current generation of Hitzfields has paved the way for the next generation to continue the work.

The next generation. Lee and Beth’s grandchildren

The family has collectively concluded that for their business to succeed, they must continue to work together, realizing the moment one cannot get along with the other, they will start to crumble. They believe that working together and staying together is a choice that they must make every day. Simply put, they choose to get along. Like other families and coworkers, they have routine disagreements, but always come to a resolution in the spirit of “Selfless Leadership.”

The family members agree the real unsung hero of the family is Beth. Although she is rarely in the public eye, never seeking attention of any kind, and always working quietly behind the scenes, her sacrifices have allowed the others to shine and to grow to their full potential. However, as a good mother does, she always keeps her sons and husband well-grounded and never allows “their heads to get too big for their hats.”

Today, Seven Sons, is a model for what can be done by scaling regenerative agriculture and producing the highest quality pastured proteins—a prime example of what others can do, if they so desire. Counting the seven sons and three of their wives, this farm of just over 500 acres now supports 47 full-time employees, which has a major positive impact in the local economy.