Wilson Land and Cattle Company - Tionesta, Pennsylvania

Russ and Lennie Wilson own and operate Wilson Land and Cattle Company in western Pennsylvania, Tionesta, Forrest County. Theirs is a first-generation operation but extending to the next generation looks quite promising. Their son, Walker, age 13, and daughter, Emmie Lou, age 11, are both actively involved in farm operations. Russ says their children love the farm in large part because they don't know what it's like to farm conventionally, performing laborious chores like putting up hay, since Russ sold all the haymaking equipment years ago. Russ says the children have a hard time understanding why other farmers are out working on their tractors all day long.

Russ and Lennie on their Saddle Donkeys

Wilson Land and Cattle Company is a diversified livestock operation on 224 acres, of which 150.4 acres are grazable and 62 acres are in timber. The remaining acres include 6.6 acres of riparian areas that are only lightly grazed, 4 acres for the barnyard, buildings, and dwellings, and a one acre pond. Russ even grazes around the buildings on their place; he hasn’t started a lawn mower in five years. Stitzinger Road, an unpaved road maintained by the County, bisects the farm. The main farm with 120 acres is on the east side with the remaining 100 acres on the west. The county road doesn’t affect the grazing management, and the Wilsons are able to move the livestock where they are needed the most.

Walker and Emmie Lou with their Favorite Donkey

They have chosen to have no cropping enterprises, instead dedicating all available acres to grazing. They also lease a 15-acre farm located about 1.5 miles away which they strictly graze. The leased land has perimeter fencing all around. Grazing on the rented land requires careful coordination with calving dates and help to get them moved there.

The farm has no hired employees or staff. Russ reports that they have tried hiring additional help, but it didn’t work out. As the children get older, they are assuming increasing responsibility, which frees Russ and Lennie to pursue other opportunities.

The infrastructure in place includes perimeter fencing around all fields with ample watering points. Russ admits that he regrets installing interior fencing because fixed fences restrict paddock flexibility in adaptive grazing management. As a result, some of that interior fencing may be coming out. The leased land has good perimeter fencing.

About half of the farm has water lines above ground, the other has water lines underground with hydrants. Russ has developed a method of grazing using hydrants to provide water without freezing the lines that he has tested down to -24°F and 120 animal units. The water set uses a brass valve that he altered. On the pressure side of the valve he drilled and tapped a hole to accept a 1/8” needle valve that can be turned on to a drip or slow steam when temperatures are below freezing. The tank consists of a 55 gallon drum cut in half with a band that has handles on for portability. A cage around the valve protects it from being trampled on. In winter, Russ insulates the short garden hose (10’-20’) back to the hydrant with foam pipe insulation or pool noodles. The pipe of the hydrant is also insulated. With the frost-free water hydrants he has installed, Russ is able to provide water as the livestock moves. He reports that many producers have adopted this watering system with great results.

An Example of Russ' Water Infrastructure

THE AGRICULTURAL ENTERPRISES

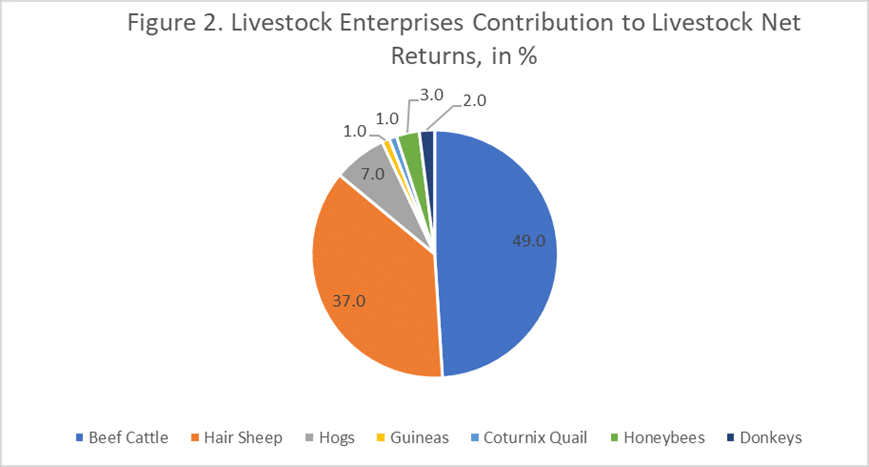

Of the diversified livestock enterprises, the primary one is the 80-90 head beef herd. These include 50 cows, retained heifer and bull calves to be sold as breeding stock, and a few steers. The Wilsons raise and breed about 80% of the heifers to sell as breeding stock. They also raise 70-80% of the bulls produced for sale as breeding stock. Most of the calves that don’t make the cut as breeding stock and are sold as feeder calves. Their feeder calves have been garnering price premiums of $0.40-$0.50 more per pound than local market price because buyers recognize how well their calves finish on grass. Calves not sold as feeders are retained, finished, and sold as freezer beef.

The Wilson weighed their cows in 2022. The average weight for their Black Angus cows was 1,016 lbs. That average includes some 1,200 to 1,400 lb cows that Russ plans to cull in 2023. They also weighed their calves at 5 to 6 months old. The average calf weight is 46% of the average cow’s body weight. He will not wean the calves until they are 9 to 10 months of age.

The Wilson Cows on Summer Pasture

The sheep flock, currently 30 head at present, is in growth mode. Daughter, Emmie Lou, has stepped up her involvement with the primarily Katahdin-based hair sheep. Her growth target is 110 ewes. The focus is on selecting commercial-hair sheep that thrive without a lot of inputs or that develop health issues such as foot rot, foot scald, sore mouth and parasite problems. This contrasts with many sheep flocks that require routine foot care and deworming. Russ admits he’s had some of those problematic sheep on the farm, but through rigorous culling protocols, he has developed a tough sheep flock that does not require deworming and hoof trimming or other extra work. While he says his flock is “nothing special,” he concedes it is quite special because they are so tough and so well-adapted to his environment.

Russ and Emmie Lou Checking Their Sheep

The Wilsons raise saddle and guard donkeys, with a herd of seven jennies and one jack. They break and train the saddle donkeys themselves. Because they have large breeds, they are rare in both roles as saddle donkeys and guard donkeys and as a result, are highly sought after. The guard donkeys serve well with both sheep and cattle, especially when coyote pressure is great. Russ made the switch from guard dogs to guard donkeys in recent years because of problems they encountered with dogs.

Additionally, Wilson Land and Cattle Company raises hogs on pasture. They buy 15-20 feeder pigs each spring, finish them out through the summer and sell the meat as freezer pork in the fall. Son, Walker, manages the finishing pigs.

Included on the farm are some poultry enterprises, consisting of chickens, quail, and guineas. At present, the birds do not get out on pasture due to tremendous predation threat. Each is a profitable enterprise, selling 400-700 guinea chicks and 400-1,000 quail chicks each year. Most buyers are local, purchasing the guineas primarily for tick control and the quail to raise for personal consumption. Russ uses social media to market his chicks, posting information about the numbers and dates available for prospective buyers. He reports that he can’t keep enough guinea chicks in stock. When asked about selling quail to area restaurants, Russ replied that the nearest larger city with such markets, including farmers’ markets, is two hours away, which presents marketing challenges. They also raise some broilers for personal consumption and for sale to local customers.

Russ keeps about 10 hives of honeybees on the farm. Because of the flora diversity, the bees thrive, adding yet another income stream.

Other ag-related enterprises include speaking to producer groups and other audiences about regenerative agriculture. Russ is building on his experiences by consulting with producers to assist them in their transition process from conventional to regenerative production. He consistently advocates for regenerative agriculture and the healing of the soil, no matter the venue. Russ has a YouTube channel that focuses on regenerative topics and admits that, when he started down the regenerative path in 2012, he never imagined he would be presenting in front of groups. He stepped into his role of spreading the word and sharing the knowledge, even as it forced him to “step outside the box.” His daughter, Emmie Lou, is already doing speaking events with Russ and she’s planning to fill in and take Russ’ place whenever he’s not able to do it anymore.

Honeybees Busy Working at the Wilson Farm

Attendees at One of Russ' On-Farm Workshops

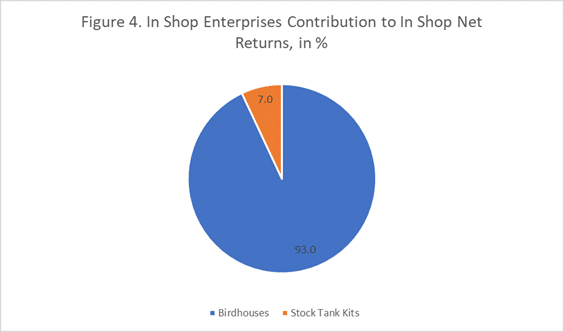

Russ' Birdhouses

To generate additional income, the Wilsons build and sell birdhouses during the down time in the winter months.

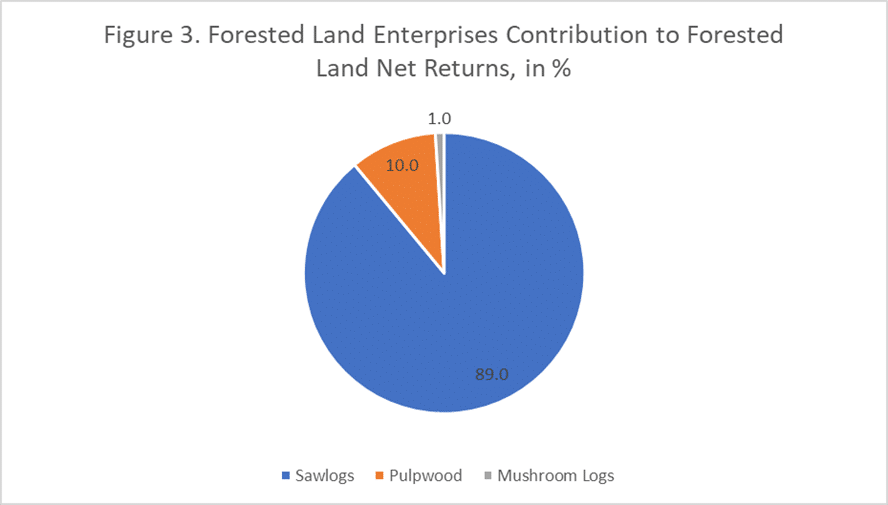

Also on site is a timber enterprise that includes saw logs, pulp wood, lumber, and mushroom logs. The Wilsons inoculate and sell the mushroom logs in 2’ sections to area customers so they can raise their own mushrooms. Russ reports that the return on investment for the mushroom logs is quite attractive.

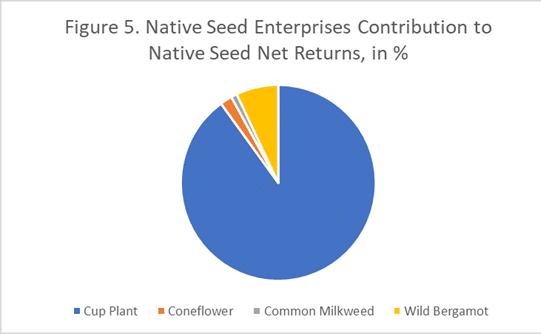

Another revenue stream is hand harvesting seed from native plant species for sale to people seeking to plant native forbs. Some of the seed he broadcasts in different areas on the farm to boost the diversity and production and some seed is sold as an additional revenue stream. Native seeds are very profitable. They hand harvest the seed, then dry it and run it through a debreader. Then it gets cleaned. They sell seed by the ounce directly to customers. For example, ten pounds of cup plant requires about 10-15 hours to harvest and clean. It sells for $8 an ounce. They have a following on social media and their website. Russ tries to post videos that include the native plants and their beneficial contributions to diversity. Many farmers and landowners buy seed to attract pollinators. Many of these native species have very good forage qualities for livestock as well. Also, since they are already adapted to their soils, these native species are better able to express epigenetic traits, which, in turn, help make them very productive.

The Diversity of Plant Species on the Farm Attract Many Different Types of Pollinators

Russ tries to add a new enterprise to his farm each year. Some enterprises work out quite well while others do not. Built into the business model is the philosophy that you can’t know what will or won’t work for you unless you give it a try. For 2023, the plan is to add silvo-pasture enterprises, for which demand seems quite strong. Trees add key diversity, so they are important to regenerative agriculture and the Wilsons plan to plant different species of trees along the interior fencing. Russ previously grew nursery trees, so he has experience and training grafting and producing nursery trees. The tree species he is contemplating producing include black locust, honey locust, black walnut, chestnut, oak, tulip poplar, apple, peach, plum, catalpa—all of which come with income-generating potential on the farm. The black walnut trees have a head start, thanks to the squirrels’ efforts, they represent the start of the family’s silvo-pasture efforts.

It is important to note that when Russ was farming conventionally, he was focused primarily on cattle and not other complementary enterprises. These additional enterprises have not only accelerated and enhanced his regenerative progress, but also his revenue streams.

BACKGROUND

Russ has been on farms his whole life. He grew up on a small, 25-cow conventional dairy farm. Both of his parents worked off-farm to support the dairy and make ends meet. When Russ was a junior or senior in high school, his family sold the dairy because they couldn’t make it work. After the farm was sold, Russ worked on five different dairies and was with each until the owners retired or went out of business. Following that, Russ took a job at a factory away from the farm, but all the while he kept his own livestock and chicken enterprises. He discovered that factory work just wasn’t a good fit, confirming his need to be outdoors.

At about age 25, he went into business for himself, starting a logging business, then a steel fabrication business—and through those years, Russ also worked as a part-time farrier.

Russ and Lennie ventured into farming together in 2008 when they leased their first farm. His philosophy is, whenever he produces something for sale, he tries to sell the highest quality possible. About 25 years ago, for example, he purchased a flock of 25 chickens for $25 each. These were rare birds imported to the USA, Barnvelders, Marans, and Wellsummers. While it seemed, as Russ put it, “A crazy, ridiculous amount of money to pay for the flock back then,” he collected the eggs and sold them as hatching eggs on the internet for $140 a dozen. Those 25 birds generated significant net returns, about $750 per month. Any eggs that didn’t sell were hatched out and sold as baby chicks for $30-$40 each. Russ says these birds are now available as chicks at most any hatchery for $4-$5 each.

As Y2K approached, Russ saw opportunities to capitalize on the doom-and-gloom predictions that projected a shutdown of the economy due to programming glitches. With the strong interest in homesteading and people producing their own food as Y2K approached, Russ bought a herd of Dexter cattle so he could market seedstock to those wanting to homestead. Dexter cattle are compact, very easy to keep and are considered to be the perfect breed for homesteading due to their size and their status as a triple-service breed (milk, meat, and oxen). During this time period, many people wanted a cow or two for meat and milk. While this was only a short-lived enterprise (five years), the Wilson’s couldn’t keep up with the demand during that period.

In 2008, Russ and Lennie bought seven Angus cows of the highest quality they thought available, at least on paper. He tried to manage the cattle like he did on the conventional dairy, but things did not work well. Beef cattle were so different from dairy animals and Russ used conventional selection tools and breeding values. As Russ put it, “It was a huge slap in the face,” as he purchased over-priced registered stock and selected his bulls based on EPDs, focusing specifically on high-carcass qualities. This produced cattle that fit the conventional feedlot model but did not work well for someone wanting to rely on grass-feed only production and who wanted to avoid high inputs.

They eventually gave up the lease on the farm they initially rented as they learned more about regenerative agriculture. Russ felt as though he would not be able to incorporate the changes necessary to make things work on rented land.

He and Lennie purchased their current operation in 2009. The new place was 42 miles from the leased farm and their herd was up to 12 cows when they made the move. Upon relocating, Russ purchased another group of Angus and a group of Hereford cattle. However, they continued with more conventional breeding and selection practices by using artificial insemination, selecting bulls specifically for each cow, with the goal of high-carcass quality. In retrospect, Russ sees that he was selecting for the “big hippos,” the ones that couldn’t make a living unless you prop them up with loads of inputs.

THE TRANSITION TO REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE

Farm survival was a key motivating factor in Russ’ decision to transition to regenerative agriculture. In 2010-2011, Russ realized he was in serious financial trouble. With his current beef herd management, he realized he could not generate adequate net returns to survive. Farming the way all his neighbors farmed, which included putting up hay, growing corn, grinding feed, feeding the cattle almost six months of the year, etc., just wasn’t working. He knew he had to make some drastic changes. In search of a better way, he called his local NRCS office and invited them out. Thankfully, Tim Elder, the grazing specialist who visited the farm, was an out-of-the-box thinker. As Russ explained his goals and what he wanted to do, Tim challenged him to consider moving his cows once a day to new paddocks to graze. At the time, Russ thought he was rotational grazing since he was moving his cattle every week or two. Though Russ didn’t tell Tim upfront, Russ admits he thought the guy was crazy. Tim has since retired from the NRCS. They remain good friends.

Russ started researching the concept of moving cattle more frequently. He learned that moving the cattle daily can indeed boost grass production, just as the grazing specialist had said. He didn’t think of it as “regenerative,” he was just searching for strategies to boost farm profitability. Russ and Lennie started moving their cows once a day and they saw immediate results.

About that time, Russ was hearing other producers talk about selling hay equipment and buying hay instead. It seemed an uncomfortable prospect to Russ, wondering what he would feed his livestock. He was grazing only about 160 days and feeding during the rest of the year, which represented a lot of purchased hay.

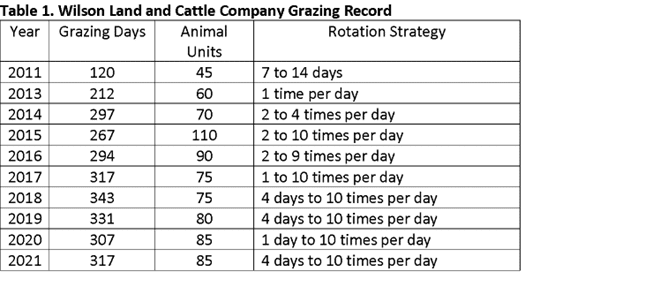

They continued to do their research on rotational grazing. According to his grazing records, and before his transition to regenerative (or adaptive) grazing, Russ had 120 days of active grazing in 2011 by using a once-per-week to once-per-two week grazing rotation. They could only support 45 animal units on the entire farm. In 2013, simply by moving the cows once per day, they increased their grazing days to 212 days, grazing 60 animal units. In the fall of 2013, Russ and Lennie set a goal of 300 grazing days per year. He encourages others to set their goals just slightly out of reach. It wasn’t until the fall of 2016 that Russ realized his goal was too low, and he upped his goal to grazing 365 days a year. Today, they move cows 2-9 times per day. This one shift in grazing management has effectively doubled the carrying capacity of the farm.

Russ stresses that the number one principle of regenerative agriculture is that soil health comes first. To that end, they move their cows a minimum of twice a day now and the sheep, once a day to every other day. They have also started planting several fields to summer annual cover crops. A typical cover crop mix includes multiple species, including: gray stripe and oilseed sunflowers, sorghum, sorghum sudan grass, sudan grass, red and white clover, annual ryegrass, Japanese and foxtail millet, chicory, and radishes.

Russ is committed to recycling as much of the dry matter produced back into the soil as possible because he knows if he absolutely must, he can re-graze after only 30-40 days of rest. However, such short rest periods are uncommon as most pastures are rested 100-120 days.

He still puts in long days, up every morning by 4:00 am, but now he uses those early morning hours to do research, seeking ways to increase efficiency and productivity. When the sun comes up is when he goes out to start “working.” This new time flexibility has been a welcomed change.

Russ recognizes that he would no longer be farming had he stayed on the conventional path and that, for them, there’s “no going back from regenerative agriculture.” In Russ’ opinion, regenerative production methods are the way to go for small and medium size operations. He is convinced it is scalable to large operations as well (and he is correct). Since starting down this path, Russ has been reaching out to other producers to encourage them to make a transition. He wants the planet to heal and thrive for generations to come and feels that if he can make the planet a better place for future generations, including his children and grandchildren, he has left a good legacy.

Russ says he’s now reaching out more to consumers because he sees the massive disconnect between consumers and where their food is sourced. He wants to educate consumers, as well as farmers, about the environmental, ecosystem, climate and human health aspects of regenerative agriculture. He believes providing consumers with more perspective regarding how and where their food is produced is important, especially when it’s compared to commodity production. Russ recognizes that regenerative production is “earth friendly” and he enjoys building connections to tell the story of regenerative production practices.

KEY ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

Russ has been farming regeneratively with intense focus since 2012. Adapting his cow herd management, and more recently the sheep flock, to the regenerative process has been part of his steep learning curve. Whenever he started adaptively grazing, he had to shift his thinking, focusing on cutting input use due to cost. He expected to lose a lot of the cows out of the herd due to an increase in the number of open (unimpregnated) cows. He anticipated a drop in cow body condition and fertility rates due to reduced consumption of supplemental feed. Russ estimates that in that first year he culled 20% of the cows out of the cow herd, reflecting his philosophy that you don’t keep cows in the herd “just because.” “If a cow is open, she goes,” he says.

His animals now have completely different characteristics than prior to the transition to regenerative agriculture. Previous cows would starve to death if they were on the farm under current practices. The culling practices implemented were strict but Russ feels he really didn't have any other choice because he wanted to get things switched over as quickly as possible. He was simply losing too much money at the time. Russ took his cow herd from a BIF frame score of 6-7 down 2.5-3 with heightened selection.

They accomplished the shift in cow size by connecting with a producer who was breeding with “old time” Angus blood. He traveled extensively, gathering up all the semen that he could find, including frozen semen from back in the 1960s. That semen was still in the old glass ampules, not in straws. Russ bought semen from the smallest frame, best looking bull that he had and incorporated that bloodline into his herd. And that bull, Russ reports, really did a wonderful job at taking the frame score down in the resultant offspring and in increasing efficiency. They did some line breeding with that same bull to continue modifying the herd genetics.

Today, none of the livestock are dewormed or receive any sort of supplemental feed, like alfalfa pellets or protein tubs, even when they are out grazing through 30 inches of snow. They select for resilience and toughness. Russ hears of other regenerative producers who must provide supplemental feed to their herds with alfalfa cubes or cake, in addition to their stockpiled forages. He chooses to stick to his strict cull guidelines: if a cow can’t handle it, she goes. Russ feels his cow herd is now amongst the toughest and most resilient in the country. They cull for many things—failure to rebreed, cows whose mineral consumption is too high, lameness, health issues, excess heat stress, etc.

Russ says his culling pressure has eased in the last five years as they’ve removed cattle that simply did not perform on minimal inputs. For example, consider a cow who has trouble calving and they have to pull a calf (dystocia issues). If that cow remains in the herd, chances are her offspring will also likely have dystocia problems, so Russ says why not just eliminate the source of the issue quickly?

Underlying his strict culling protocols, Russ stresses that the soil comes first, hence his focus on soil health and the importance of nutrient cycling. He sees the importance of cycling nutrients back into the soil as quickly as possible to feed the microbes and to encourage plant growth. When the cow herd is off in the shade much of the day, that job is not being done efficiently. Heat tolerance in the cow herd is another trait characteristic that supports Russ’ goal. He deliberately keeps his herd in full sun as much as possible, limiting its access to shade. His objective is to have the nutrients (from manure and urine) evenly dispersed across each pasture or paddock by keeping the cows out in the paddocks all day. If they are seeking shade frequently, then the majority of the nutrients will be deposited in the shade and by the water source. This is exactly where the nutrients do not need to be and where they would create nutrient overload.

Russ follows a similar cull strategy with his sheep flock. Basically, if the livestock require too much work, Russ says they need to find a new home.

Russ chooses not to have standard soil tests done on his farm routinely primarily to cut operating costs and feels their observations in the field, walking fields and digging in the soil, are sufficient for making fertility assessments. He stresses he is not going to apply fertilizer and lime. With his philosophy that the soil comes first, Russ does what he feels is best to improve the soil. In short, he is not sure standard soil testing would convince him to operate differently.

When he performed soil tests previously, he pulled 43 samples, which proved quite costly. Several years ago, Russ tried to get the results of organic soil tests interpreted (as opposed to conventional soil tests which isolate on inorganic nutrient availability) but he couldn’t find anyone to interpret the results. The last conventional soil test indicated that 37 of 43 fields sampled were phosphorus and/or potassium deficient. Russ is convinced that had it been an organic test, the outcome would have been drastically different because the plants don’t indicate such deficiencies. Instead, he believes that the microbes in the soil are making those nutrients available to the plants. Based on the work of Understanding Ag, Russ is correct that very few soils are truly mineral deficient. A Total Nutrient Digestion Test (TND) usually reveals that mineral stores in the soil are sufficient but tied up due to poor soil biology. Correcting the soil biology usually solves the mineral availability and uptake problem.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THOSE CONSIDERING REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE

Russ recommends that producers considering starting down the regenerative path be aware that one of the biggest challenges to making the switch is mindset. He remembers the uncomfortable feeling of sending his haymaking equipment down the driveway, wondering how well he would do without the hay he would no longer be putting up. Russ knew he was stepping outside the box into unfamiliar territory.

“Adopt the mindset and approach that moves you beyond status quo thinking,” he says, “and don't be afraid to step outside the box and feel uncomfortable despite the peer pressure around you.” As a result of this approach, Russ sees Wilson Land and Cattle Company as one of the leaders in his region. Though they are doing this by themselves, Russ knows his neighbors are watching and his approach has been to consider what others suggest with a grain of salt. If he likes something, he tests their suggestions on a small scale and monitors the outcome to see if he can make it work.

Russ acknowledges, as human beings, we resist change, we don't like to step outside the box. We want to stick with the norm. But his suggestion is to “do it” and to not be afraid to switch to regenerative practices. “Learn as much as you can and then jump in,” he says. There are so many pluses to regenerative agriculture, but adopting a new mindset, like not putting up so much hay or adopting and implementing adaptive grazing practices, is key. Russ knows many producers who are interested in regenerative production, but they are reluctant to start moving their livestock daily or to implement the other principles of regenerative agriculture. They hesitate because they have not yet altered their way of thinking. They don’t initially understand how moving livestock daily can make such a significant difference compared to moving only once per week or once per month.

Russ encourages livestock producers to not be afraid to get out there and move their animals much more frequently, at least once a day, even in face of perceived barriers. For example, many producers work off the farm, which can present challenges. Working 8-10 hours per day with an hour commute each way can add up to a 12-hour, off-farm work day. In those cases, the producer can set their paddocks for the coming week on the weekend and then simply let the livestock into the next paddock upon returning home at the end of their workday, which takes just a few minutes and allows the producer time to observe the livestock. Or, with the paddocks set each weekend, a spouse or even a high school-aged child can move the livestock to the new paddock each day (which is a good source of extra income and experience for a high schooler).

In terms of managing herd traits, and selecting for tough, resilient, smaller framed cows, Russ doesn’t recommend everyone “just jump into the process full bore without considering all the consequences.” This is because they can expect more-than-normal open cows, and will need to be prepared to cull harder initially. Many livestock producers may want to approach it more slowly than he did.

Russ also recommends finding strategies and tools to increase ease and efficiency. He suggests automated latches as a way to pre-set moves of the livestock daily, or even multiple times per day. This can be accomplished by using Batt Latches or PensAgro Fence Raisers.

Russ says producers don't need to spend thousands of dollars to try things on a small scale and provides this example: When he considered putting native, warm season grasses on the farm, he wasn't sure it was a wise move. So, to test the strategy, he seeded four 2’x 6’ plots of native, warm season grasses in his backyard. After successfully experimenting on that small scale, he decided to scale up and establish those native grasses on a broader scale on the farm.

A strategy Russ recommends to crop farmers is testing interseeding cover crops in corn—again, keeping it small scale, only on an acre or two initially, not the whole farm. And if it doesn't work the first time, try it again, or even multiple times if necessary. Russ stresses to producers to not just try something once and conclude it won’t work. Instead, embrace the learning curve, he says, make adjustments and try it again.

Russ also advocates keeping a control or baseline, for comparison, when testing things, rather than just going full bore. In fact, Russ still has control areas here and there on his farm. While they are not as large as they were (just four, one-quarter acre areas where they have not applied any seed, lime, or fertilizer), these controls provide a good comparison.

KEY POINTS OF PROGRESS AND SUCCESS

When asked his biggest surprise from the transition to regenerative production, Russ listed two, increased farm productivity and improved animal health. Their animal health is just exceptional now, in contrast to when they routinely had a veterinarian out to treat livestock for pneumonia and hoof rot. They don't call the vet anymore unless there's been an accident, like an animal getting tangled up in wire and cut. In fact, the last time they had the vet out to their farm was when a jack got kicked in the shoulder when he was breeding a jenny, and his shoulder needed a few stitches.

Another example of improved livestock health centers on reproduction. In the past, they suffered too many abortions. Deer and raccoon populations are great enough that they have had problems with neospora, for which there is no good treatment. Previously, some cows would abort at 5-7 months. Thankfully, they haven't faced that issue for some time now. Grazing adaptively and improving soil microbial performance makes a significant difference in most animal health challenges, which is a consistent benefit reported by regenerative graziers. It is also one of the hardest things for skeptical farmers to accept. They simply cannot understand how better soil microbial life, plant species diversity, and frequent movement of the livestock make such a dramatic difference. That is, until they do it themselves. The evidence is strong that if you improve soil biology, you improve the mineral cycle. Plants that are more mineral-rich provide a higher level of nutrition to the livestock in every bite. Greater plant species diversity significantly increases phytonutrient content in the plants the livestock eat. These phytonutrients are rich in secondary and tertiary nutrient compounds that are also medicinal and anti-parasitic in action. Daily movement keeps the livestock moving away from internal and external parasite hatches, provides better nutrition, and prevents the livestock from having frequent contact directly with the soil.

Russ believes that adapting livestock to a given environment, location, and system is key to the improved performance and animal health they’ve experienced. The best livestock on a farm are those born there, which is an important way to capture epigenetic benefits. Russ’ cow herd is closed, all cows and bulls were born on the farm; they are moving in that direction with the sheep flock as well.

According to the “experts,” with good management, Russ should expect to produce only about 6,000 pounds of forage dry matter per acre for the soil types represented on his farm. Yet his results tell a different story. He has some fields producing 9.5 tons of forage dry matter yields per acre without added fertilizer, lime, or irrigation. This contrasts with his prior management where he spent as much as $26,000 per year on fertilizer alone. His ground is well managed now, but in a very different way.

Russ attributes the improved performance he has built into his operation through enhanced diversity as key to his improved financial and economic performance. In years past, many of Russ’ pastures had about three dominant grass species, which Russ considers no better than a monoculture. He started interseeding pastures with native warm season grasses, forbs and legumes to increase diversity. In one field he planted, a native grass mix developed collaboratively with a conservation seed company, he applied no lime or fertilizer and no irrigation. Russ did a total dry matter yield test on that same pasture and found it yielded 24,000 pounds of forage dry matter in one year, again, with no lime and no fertilizer. Admittedly, that was all of the dry matter that was available. He estimates they likely harvested about 50% of that, with the other 50% recycled back into the soil to improve soil health and to increase resilience.

The Forage Biomass Production has Grown Significantly

Increasing forage dry matter yields from 6000 lbs/ac up to 24,000 lbs/ac is a four-fold increase. The more acres on which you can accomplish that across a farm, the more carrying capacity you create. In time, Russ will be able to carry four times the number of animals that his neighbors’ pastures can support. And he can do that with far fewer purchased inputs.

Russ says his farm is much more drought tolerant now, and the snow doesn't bother them so much either. Their soils don't freeze as deeply as they used to because of the improved aggregation (air space) in the soil. Before the transition to regenerative agriculture, they had to use a rubber hammer at times to set step-in posts in the winter. The posts go in easily now. Likewise, when the soil was too dry, they had problems with step-in posts. This is the first year that it was not a problem.

Russ has been managing the soil such that the organic nutrients will be available when the plants need them. He has been expecting the farm to plateau, in terms of soil health and productivity gains, but he said that Dr. Allen Williams, of Understanding Ag, assures him that the farm will never plateau, but that it will continue to improve every year. For Russ, thinking about the farm’s future, that’s an extremely exciting prospect.

Russ's Cattle Enjoying a Winter Day at the Farm

When asked if there were any unwanted surprises Russ couldn’t think of any. He’s more profitable while working fewer hours. The livestock are healthier and he’s producing more grass. And he’s diversifying using the same land base. While others may have experienced a downside in their respective moves to regenerative production, in Russ’ experience, there were none. The Wilsons are seeing more species in the field, more diverse swards of forages, and all that goes with it, including diverse bird, wildlife, and insect populations.

Russ reports sighting three new bird species that he’s seen on the farm just in 2022. And every year he takes pictures of the insects that he doesn’t recognize to get them identified by experts. He regularly sees new insect species and more insects, in general, most of which are beneficials. He says it's great walking through the fields, seeing so many insects—something he hadn’t experienced for a long time. On his farm, Russ wants as many insects as possible.

When the Wilsons farmed conventionally, they relied on Lennie’s off-farm employment to cover family living expenses. Since transitioning to regenerative farming, she’s been able to quit her off-farm job because the farm now fully supports the family.

PRODUCTION AND FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE

The average Soil Organic Matter (SOM) when they moved onto the farm was about 2.5%. Russ is due to test in 2022 or 2023, but in 2020, the SOM observed in their fields averaged 4.5% and ranged from 3.75%+ to 5.0%. Overall, SOM has increased dramatically across the farm with productivity increasing as a result. Water infiltration has also increased from less than 10 inches per hour to over 60 inches per hour. Russ aptly calls it “mind boggling.”

Before transitioning to regenerative agriculture, Russ was using 3,500 gallons of diesel fuel for farm operations each year. By making the decision to stop putting up hay and to cut his fertilizer use, he cut his diesel use to just 200 gallons annually, which is only about 6% of what he used previously. At the national average diesel price, $5.313 per gallon, reported on November 14, 2022, that amounts to annual savings of over $17,500, just for diesel. He is also saving what he had been spending to wrap his hay, another $2400 each.

Soil Aggregate Test at Russ’ Farm Showing the Benefits of Soil Biology

Since 2011, Russ has steadily increased his grazing days, going from just 120 grazing days to more than 300 grazing days per year (Table 1). In the four-year period from 2018-2021, he averaged 324 grazing days per year. That is a 270% increase in grazing days per year in just a decade. Adaptive grazing strategies and multiple moves daily, instead of moving only once every 1 to 2 weeks, rotation to multiple moves daily, have made a significant difference. Most grazers consider themselves to be doing a really good job if they are moving their livestock to fresh pasture every week or two. While that is far better than no rotation at all, it does not make a major difference economically, or from a forage biomass production standpoint. Only when Russ started making daily moves did he begin to make substantial progress.

In 2018, Russ reported 343 grazing days with 75 animal units. Their eight-year average is 309 grazing days. The number of animal units was down some because of opportunities to market beef at a premium price. Demand was strong for the Wilson’s cattle because of their ability to perform on just grass. Their herd size in 2022 was 80 head with 50 mama cows. Russ’s goal is 70 mama cows, but the offers for his breeding stock have been too attractive to turn down, so he has been selling more animals than he would normally. Even through 2022, Russ has found it challenging to produce enough breeding stock to grow his herd.

A point of clarification for the rotation strategies listed in Table 1 is in order. A couple of recent years list the rotation strategy of 4 days to 10 times per day. The 4-day option is specifically for when the Wilsons are out of town on family vacation. They plan several trips per year in which they take their mules and donkeys riding for four days at a time. He does not ask anyone to come check animals while they are away. Instead, they set things up for the livestock for five days and go on vacation for 4 days at one time.

During the last couple of years, they’ve moved the cow herd an average of twice per day. In 2023, they plan to increase that average to four moves a day. They see great benefit from moving more frequently. The decision to move is determined greatly on what the field needs.

When Russ compares current annual cow feed maintenance costs from 2011 to now, he understands why he would never return to the way he used to do things (Table 2). His estimated cost for the standing forage is $0.03/lb (DM basis). If his average cow is consuming about 30 lbs per-head per-day on a DM basis, then his cost/hd/day is about $0.90. Since 2018, Russ has averaged 324 grazing days annually. That equals a cost to feed his cows for that 324 days of $291/hd and he would only have to feed those cows for 41 days of the year. Using hay and a protein supplement, at $140 per ton for hay and $360 per ton for supplemental crude protein, the cost per head would be $3.02 per day (accounting for hay cost, protein cost, and feeding cost). This would be about $124 per head per year. That is a total cost per cow per year of $415 (Table 3).

| Table 2. Costs per Day for Feeding Cattle. | |||

| Item | Cost/Lb | Lb/Hd/Day | Cost/Hd/Day |

| Standing Forage* | 0.03 | 30 | $ 0.90 |

| Hay** | 0.07 | 30 | $ 2.10 |

| Supplemental CP** | 0.18 | 3 | $ 0.54 |

| Cost to Feed*** | $ 0.38 | ||

| Total Feeding Cost: | $ 3.02 | ||

| *Standing forage valued at $0.03/lb and requires an average of 30lbs/hd/day on a dry matter (DM) basis. | |||

| **Hay price: $140/ton; Supplemental CP: $360/ton | |||

| ***Cost to Feed cost includes labor, tractor fuel, maintenance, etc. | |||

| Table 3. Total Costs for Feeding Cattle, $ per Cow per Year, Given Days Grazing | |||

| Days Grazed | Days Fed | Total Feed Costs | |

| Before Regenerative Agriculture | 120 | 245 | |

| $ 108.00 | $ 739.90 | $ 847.90 | |

| After Regenerative Agriculture | 324 | 41 | |

| $ 291.60 | $ 123.82 | $ 415.42 | |

| Russ's Grazing Goal - 365 days | 365 | 0 | |

| $ 328.50 | $ - | $ 328.50 | |

Contrast that to 2011 when he was only able to graze for 120 days annually (a cost of $108 per head annually). He would then have to feed the cattle the remainder of the year, or 245 days, which would cost $740 per head annually for a total cow feed maintenance cost of $848/hd annually. A cost differential of $433 per cow per year gained simply by moving the cows daily compared to once a week. Russ’s goal is to graze 365 days; his total cost to feed his cows will be less than $330 per head per year when he accomplishes that goal.

The argument is often made that the increased labor needed to build temporary paddocks and move livestock daily more than offsets any economic benefits. The fact is there is no basis to this argument. You are simply trading labor for labor to a certain extent. Russ no longer spends substantial portions of his summer cutting, raking, and baling hay and he does not have to maintain haying equipment. In addition, he does not have to haul hay out of hay fields just to haul it back again in the winter to feed livestock. Also, he is not mining nutrients out of hay fields nor relying on purchased fertility to keep hay production going.

He is now able to devote time to careful observation of his livestock and pastures daily, and to making better management decisions. The time it takes to construct a temporary paddock for 85 head of cattle is about 15-20 minutes at the most each day. Russ makes money by taking the time to do this compared to spending money to make hay.

Russ can now run 85 head versus the 45 head he was running in 2011. His records show that he is now running twice the number of head of cattle on the same acres compared to 2011, plus he is doing that at roughly 50% of the former annual cow costs.

When Russ was farming conventionally, all he had time for was the cows, putting up hay, planting, harvesting, grinding and mixing feed, hauling and spreading manure. There simply was no time to do anything else on the farm. Now? He’s still busy, but with the diverse set of enterprises they have going, everyone in the family stays busy. The key difference is, now they choose to be busy. Russ says he has time to graft trees, harvest native seeds, inoculate mushroom logs, etc. He moves their cows multiple times daily, including all that goes with it— setting fence, moving water, pulling fence—in an hour and a half per day. That frees up the rest of the day to commit to other business and management activities. In contrast, when farming conventionally, Russ was working 16-18 hours a day, especially when putting up hay. Now he only works during the daylight hours.

Net Returns by Enterprise:

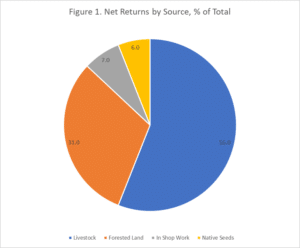

Russ and his family have multiple streams of revenue created through the various enterprises they now operate on the farm. The revenue streams are divided into four main categories of enterprises:

Livestock: Consists of beef cattle, hair sheep, pigs, donkeys, chickens, guineas, quail, and honeybees.

Woodland: Saw logs, Pulpwood, Mushroom Logs

In Shop Items: Bird Houses, Stock Tank Kits

Native Seeds: Cup Plant, Coneflower, Milkweed, Wild Bergamot

Figure 1 shows the percent of total farm revenue generated by each enterprise category. The livestock sector generates the largest percentage of revenue at 56%. The woodland generates the second highest revenue at 31%. The In-shop manufactured items (7%) and the Native seed (6%) round out the on-farm revenue streams.

Figures 2 through 5 break down the specific revenue generated by each enterprise within the four enterprise categories.

SUMMARY

Russ and his family are a great example of how small farms can still generate a good living for a family. His prior attempts at farming on a small scale demonstrated that conventional approaches rarely work when seeking a full-time living. However, when he transitioned to a regenerative approach and the introduction of multiple complementary enterprises, things began to come together.

Before transitioning to regenerative Russ was just like the majority of farmers producing livestock in his region. He was 100% beef cattle (one livestock species) and was going broke fast. There was no feasible way to make a living solely from the farm.

After transitioning to regenerative principles and practices, Russ had more time for incorporating diversity in enterprises. That was a major game changer. Using the same acres to support several revenue streams that are synergistic with soil health and ecosystem health goals produced good results and now allow Russ and his family to devote their time to the farming enterprises.